20 Best Movies Like A Clockwork Orange | Similar-List

Table Of Contents:

- 20 Best Movies Like A Clockwork Orange

- 1. Ichi the Killer (2001)

- 2. Scum (1979)

- 3. Dogville (2003)

- 4. Cape Fear (1991)

- 5. American Psycho (2000)

- 6. Irreversible (2002)

- 7. Trainspotting (1996)

- 8. Brazil (1985)

- 9. Taxi Driver (1976)

- 10. Fight Club (1999)

- 11. Man Bites Dog (1992)

- 12. Natural Born Killers (1994)

- 13. Pulp Fiction (1994)

- 14. Joker (2019)

- 15. No Country for Old Men (2007)

- 16. Hate (1995)

- 17. Bronson (2008)

- 18. Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984)

- 19. Seven (1995)

- 20. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

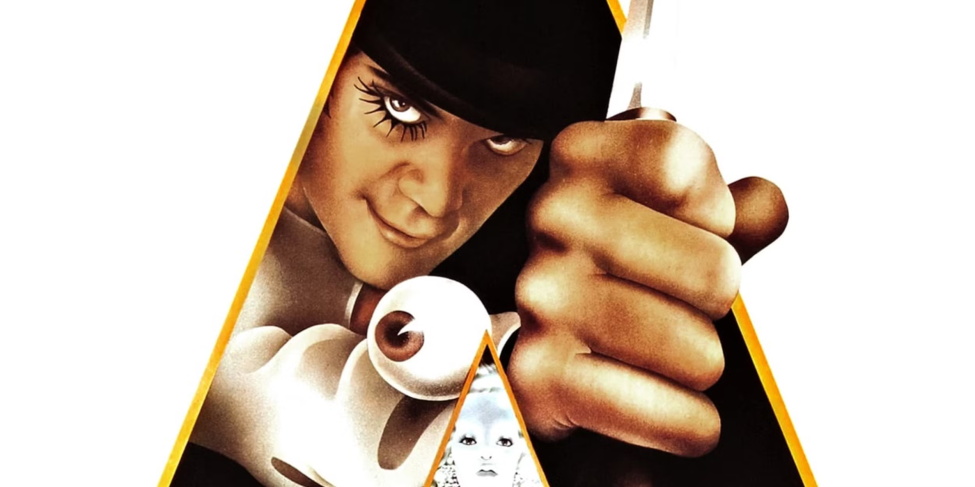

Stanley Kubrick’s "A Clockwork Orange" (1972) is not just a film; it is a cinematic experience that provokes deep reflection and intense discussion. Blending striking visuals with a haunting narrative, the film delves into controversial themes like violence, free will, and moral ambiguity. Centering on the notorious character Alex DeLarge, portrayed masterfully by Malcolm McDowell, it critiques societal standards and institutional power structures.

Even after decades, "A Clockwork Orange" remains relevant, continuing to ignite conversations around media ethics and behavioral implications in society. It serves as a pivotal piece in the exploration of human nature under pressure. For those intrigued by its unsettling insights, we present twenty other films that explore similar themes and dilemmas.

20 Best Movies Like A Clockwork Orange

1. Ichi the Killer (2001)

Ichi the Killer, directed by Takashi Miike, is a film that stands as a stark emblem of extreme cinema. Based on the manga by Hideo Yamamoto, tells the harrowing story of Ichi, a disturbed and psychopathic killer driven by his unresolved traumas and twisted perceptions of love and masculinity. The film dives into the murky waters of sadomasochism, violence, and the dark recesses of the human psyche, plunging viewers into an unsettling yet captivating experience.

At the core of Ichi, the Killer is the disturbing relationship between Ichi and Kakihara, a sadistic yakuza enforcer who thrives on pain and seeks the thrill of being in a life-and-death dynamic. Kakihara’s relentless pursuit of Ichi not only highlights his depraved nature but also reflects on the thin line between pleasure and pain, domination and submission. This complex relationship leaves the audience questioning the nature of victimhood and agency, similar to the themes explored in "A Clockwork Orange."

The film is notorious for its graphic depictions of violence, characterized by Miike's signature style. From gruesome dismemberments to psychological torture, the visceral imagery serves not only to shock but also to push boundaries regarding how violence is portrayed on screen. The use of vibrant colors and surreal cinematography contrasts sharply with the horror of the content, creating an almost dreamlike atmosphere that enhances the surreal experience. This juxtaposition invites viewers to grapple with their discomfort, thus engaging them in a conversation about the implications of violence in media—much like the moral inquiries raised by Kubrick.

Moreover, Ichi the Killer challenges the conventions of traditional narrative structure. Instead of offering a linear storyline, Miike weaves together fragmented sequences that allow for deeper character exploration and a more psychological approach to violence. The storytelling emphasizes the chaos and confusion that often accompanies trauma, compelling the audience to confront the psychological underpinnings of Ichi's actions. This thematic depth transforms the film from mere exploitation into a thought-provoking commentary on human nature.

As a cult classic, Ichi the Killer has sparked intense debate about ethics in cinema, censorship, and the implications of showcasing extreme violence. It acts as a mirror reflecting society's fascination with brutality while simultaneously critiquing that fascination. Just as "A Clockwork Orange" prompts viewers to consider the ramifications of desensitization to violence, Ichi the Killer challenges audiences to confront their responses to brutality and psychological manipulation.

In essence, Ichi the Killer is not just a film intended for shock value; it is a deeply layered exploration of violence, identity, and the human condition. Its audacious approach to storytelling and unflinching examination of dark themes solidify its place as an essential watch for those drawn to films that provoke deep thought and emotional reaction, much like Kubrick’s iconic work.

2. Scum (1979)

Scum, directed by Alan Clarke, is a harrowing and unflinching portrayal of life within a British juvenile detention center. Originally made for television, it faced significant censorship before being released as a feature film due to its stark depiction of violence and the brutal reality of institutional life. The film is a raw commentary on the failings of the juvenile justice system and the psychological effects of confinement on its residents.

The narrative focuses on the character of Carlin, portrayed by Ray Winstone, who arrives at the Borstal institution as a young offender. Carlin quickly strives to assert control in a brutally hierarchical environment marked by gang violence, corruption, and severe mistreatment from the guards. His determination to survive and ultimately resist the oppressive system serves as a critique of authority and societal neglect.

One of the film’s most striking features is its realistic portrayal of violence. Unlike conventional representations that often glamorize or sensationalize brutality, Scum presents it in a stark and unsettling manner. The brutality is visceral and relentless, underscored by a documentary-style approach that immerses the viewer in the harrowing experiences of the characters. The graphic fight scenes and acts of aggression emerge not just as moments of shock but as vital components of the oppressive social structure that governs the boys’ lives.

The film's unvarnished depiction of systemic abuse extends beyond the inmate interactions. The guards often resort to physical and psychological violence to maintain control, showcasing the cycle of power and domination that operates within the institution. This reflection on authority parallels the themes found in "A Clockwork Orange," where violence is both an expression of individual agency and a reaction to systemic oppression.

Scum also explores themes of camaraderie and betrayal among the inmates, offering a poignant look at how friendship can provide fleeting solace in a hostile environment. The boys form fragile alliances, revealing the complex dynamics of survival in such a brutal setting. Yet, as Carlin rises to power within the Borstal, his relationship with his peers becomes strained, illuminating the morally ambiguous choices that individuals must make amidst extreme circumstances.

The film’s impact has resonated with audiences and critics alike, prompting discussions about the treatment of young offenders and the broader implications of institutional violence. Its controversial nature sparked debates about censorship, representation, and the moral responsibility of filmmakers to depict harsh realities.

Ultimately, Scum is a chilling exploration of the human condition when faced with dehumanizing systems and societal neglect. Clarke’s masterful direction and Winstone’s compelling performance render it a profound commentary on the cycle of violence and psychological trauma. As such, it acts as a crucial companion piece to Kubrick’s "A Clockwork Orange," echoing the vital questions about freedom, morality, and the effects of systemic oppression on vulnerable individuals.

3. Dogville (2003)

Dogville, directed by Lars von Trier, is a daring and provocative exploration of morality, community dynamics, and human nature set within an unconventional narrative structure. Filmed on a minimalistic stage with distinctly drawn chalk outlines to represent buildings and locations, the film eschews traditional cinematic realism, prompting audiences to engage with its themes on a more conceptual level.

The story centers on Grace, played by Nicole Kidman, who seeks refuge in the small and isolated town of Dogville while escaping from mobsters. Initially welcomed by the townsfolk, her presence prompts a spiral of events that reveal the darker aspects of human nature masked by a facade of neighborly kindness. The film starkly illustrates how quickly shared morals can dissolve when personal interests and fears come into play, inviting viewers to reflect on the fragility of community ethics.

One of the most gripping aspects of Dogville is its commentary on power dynamics and exploitation. As Grace seeks acceptance and integration into Dogville, the townspeople begin to exploit her vulnerability under the guise of assisting. The gradual erosion of their initial generosity culminates in a chilling transformation where Grace becomes an object of manipulation and abuse, illuminating themes of complicity and moral decay. This descent into cruelty cleverly mirrors societal behaviors when faced with perceived threats, posing critical questions about collective guilt and complicity in evil.

The film also employs a unique narrative device: it is divided into "chapters," reminiscent of a theatrical production. Each chapter reveals deeper moral quandaries and challenges the characters' veneer of civility. Von Trier’s genius lies in his ability to craft moments of discomfort and reflection. The minimalistic setting compels viewers to concentrate on the dialogue and interactions between characters, emphasizing the psychological dimensions of their relationships.

Dogville does not shy away from addressing heavy themes such as classism, misogyny, and the human tendency towards violence. As the narrative unfolds, Grace’s transformation from a hopeful outsider to a symbol of retribution portrays a powerful critique of society’s inherent darkness. The harsh landscape of Dogville serves as an allegory for the broader human experience, dissecting how individuals navigate moral ambiguity in the face of adversity.

The film's climax is both shocking and thought-provoking, encapsulating the idea of justice when it becomes a mere reflection of vengeance. The ending challenges the audience’s moral compass, leaving viewers to grapple with their feelings about entitlement, punishment, and the lens through which we view victims and perpetrators. By presenting a scenario that escalates from kindness to brutality, Dogville provokes essential discussions about societal values and the human condition.

In essence, Dogville stands as a powerful and unsettling examination of morality, revealing the complexities and contradictions inherent in human behavior. Its stark, theatrical style and challenging themes resonate with audiences long after the credits roll. Much like "A Clockwork Orange," it unnervingly holds up a mirror to society, compelling viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about their moral compasses and the potential for cruelty that lurks within us all.

4. Cape Fear (1991)

Cape Fear, directed by Martin Scorsese, is a masterful psychological thriller that delves into themes of vengeance, obsession, and the haunting nature of past sins. A remake of the 1962 classic of the same name, this iteration brings a raw intensity and complexity to the story, propelled by standout performances from Robert De Niro as the menacing Max Cady and Nick Nolte as the tormented attorney Sam Bowden.

The film follows Cady, a recently released convict who seeks revenge against Bowden, the lawyer who failed to secure his acquittal years earlier. Cady's relentless pursuit of Bowden and his family is not merely a quest for retribution; it evolves into a psychological battle that explores the darkest corners of human nature. De Niro’s portrayal of Cady is nothing short of chilling, as he embodies a character who is both charismatic and terrifying. His transformation—inclusive of tattoos and a calculated demeanor—reveals the depths of his psychopathy, forcing viewers to confront the terrifying reality of predatory behavior.

Scorsese’s direction enhances the film’s unsettling atmosphere, using a variety of cinematic techniques to cultivate tension and dread. From the oppressive score to the striking use of light and shadow, every frame heightens the sense of fear and vulnerability experienced by Bowden’s family. Notably, the film’s cinematography makes use of close-ups and imaginative angles, immersing the audience in the characters’ psychological turmoil. The iconic sequence in which Cady lurks in the shadows while watching Bowden’s family exemplifies the suffocating menace he embodies, serving as a stark reminder that danger is often lurking just out of sight.

A distinct thematic element in Cape Fear is the exploration of the moral ambiguity surrounding justice and retribution. While Cady’s actions are undeniably monstrous, the film invites viewers to reflect on the failures of the legal system that allowed such a predatory figure to exist in the first place. The narrative raises questions about vigilantism and the morality of taking justice into one’s own hands as Bowden grapples with the decision of whether to confront Cady directly or rely on the law’s protection. This struggle culminates in a gripping climax that forces both characters to face their pasts and the consequences of their actions—themes that resonate within the broader moral landscape.

Furthermore, the film intricately examines the impact of trauma and guilt on family dynamics. As Bowden’s past catches up with him, his family's safety becomes increasingly compromised. His wife, Leigh (Juliette Lewis), and daughter, Danielle (particularly represented in a harrowing scene at a party), are drawn into the conflict, illustrating the collateral damage of Bowden's choices and the generational ripples of violence and vengeance. The unsettling portrayal of Cady's interest in Danielle raises uncomfortable questions regarding innocence and the corrupting influence of evil.

The psychological tension reaches its peak in the climactic showdown, where the film not only delivers thrilling horror but also serves as a narrative exploration of the primal instincts of survival and the lengths to which an individual will go to protect their family. As Cady and Bowden face off against the tumultuous backdrop of a stormy Cape Fear landscape, the setting itself transforms into a character, embodying the chaos and moral uncertainty that drives the narrative forward.

In conclusion, Cape Fear stands as a haunting meditation on evil, justice, and the complexities of human behavior. Scorsese’s captivating direction, paired with De Niro's chilling performance, crafts a film that is as intellectually engaging as it is viscerally thrilling. Much like "A Clockwork Orange," it compels audiences to confront their understanding of morality and the darkness that resides within society, ensuring its place as a significant work in the psychological thriller genre. With its blend of suspense, character study, and moral complexity, Cape Fear ultimately leaves viewers grappling with profound questions about justice, obsession, and the nature of evil.

5. American Psycho (2000)

American Psycho, directed by Mary Harron and based on Bret Easton Ellis's controversial novel, is a darkly satirical exploration of consumerism, identity, and the nature of evil set against the backdrop of 1980s Manhattan. The film centers on Patrick Bateman, played by Christian Bale, a wealthy investment banker who leads a double life as a notorious serial killer. Through its provocative narrative, American Psycho delves deep into the psyche of a character who is as polished on the surface as he is deeply disturbed underneath.

Bale’s performance as Bateman is nothing short of remarkable. He portrays Bateman with a chilling blend of charisma and detachment, exemplifying the coldness that defines his character. The film vividly captures Bateman's obsession with materialism, status, and perfection, evident in his meticulously detailed morning routine that includes an array of expensive grooming products. This sequence not only establishes his narcissism but also serves as a critique of the superficial values prevalent in the yuppie culture of the era. The emphasis on luxury brands and the frantic pursuit of status reflect society's emptiness, suggesting that such pursuits mask a profound existential despair.

As the story unfolds, American Psycho takes viewers through Bateman’s increasingly violent acts, juxtaposed against the banality of his everyday life. Scenes of graphic violence are often juxtaposed with dark humor and absurdity, creating a dissonance that reveals the film’s satirical edge. Bateman’s coldly meticulous descriptions of his murders—often delivered in a deadpan manner—serve to highlight the absurdity and horror of his actions, forcing audiences to confront the grotesque reality of his character. The film raises critical questions about desensitization to violence and the normalization of brutality in society, encouraging viewers to examine how such elements are embedded in the fabric of modern culture.

The film's exploration of interpersonal relationships is equally unsettling. Bateman interacts with a cast of characters that are equally self-absorbed and superficial, including his privileged friends and romantic interests. His relationships serve as a microcosm of the era, illustrating how shallow social connections can become in a world ruled by appearances. Notably, his interactions with fellow Wall Street executives highlight a disturbing sense of competition and envy, as he relentlessly compares himself to others—a theme showcased in the infamous scene where he critiques the business cards of his peers. This obsession with status ultimately feeds into his violent tendencies, suggesting that the pressure to maintain an image can lead to a complete detachment from empathy and morality.

American Psycho also incorporates elements of psychological thriller and horror, blurring the lines between reality and Bateman’s distorted perceptions. The film cleverly plays with ambiguity, leaving viewers questioning what is real and what exists within Bateman’s fragmented mind. The surreal sequences, especially those involving hallucinations and psychological breakdown, emphasize the themes of alienation and identity crisis, capturing the sense of madness that permeates Bateman’s existence. This narrative ambiguity draws parallels to "A Clockwork Orange," where the viewer must grapple with the motivations behind antisocial behavior and the consequences of a society that breeds such extremes.

The film’s commentary extends to the role of media and pop culture in shaping perceptions of violence and identity. Bateman frequently references popular music, film, and literature, embedding his actions within a context that reflects society’s consumption of violence as entertainment. This self-awareness underscores the irony of his character; despite his monstrous behavior, he is acutely aware of societal trends—yet remains entirely without any semblance of moral grounding.

By the conclusion, American Psycho leaves audiences with an unsettling sense of ambiguity. Bateman’s fate remains uncertain, suggesting that evil may continue to thrive beneath polished veneers, hidden amidst the chaos of everyday life. This open-ended nature compels viewers to grapple with uncomfortable truths about identity, morality, and the emptiness of consumer culture.

In summary, American Psycho is a provocative and incisive examination of materialism, identity, and the dark facets of human nature. Through a combination of biting satire, unsettling performances, and psychological complexity, it crafts a narrative that forces viewers to confront the uncomfortable truths lurking beneath pristine exteriors. Much like "A Clockwork Orange," it challenges societal norms and raises critical questions about the human condition, ensuring its place as a significant film in both psychological horror and satirical commentary.

6. Irreversible (2002)

Irreversible, directed by Gaspar Noé, is an audacious and polarizing film that explores themes of time, trauma, and the nature of vengeance through a nonlinear narrative structure. Known for its harrowing depiction of violence and sexual assault, the film presents a visceral experience that challenges viewers' comfort levels and forces them to confront the raw brutality of its subject matter.

The story unfolds in reverse chronological order, beginning with the aftermath of a horrific crime and tracing back through the events leading to the violence. This unique narrative style not only heightens the sense of dread but also serves to emphasize the irreversible nature of time and the permanence of trauma. The audience is compelled to witness the moments leading up to the tragedy, creating a powerful sense of foreboding that lingers throughout the film.

Central to the plot are two main characters, Marcus (Vincent Cassel) and Pierre (Mathieu Kassovitz), who are on a frantic search for revenge after the brutal rape and murder of their partner, Alex (Monica Bellucci). As they delve into the seedy underbelly of Paris, the film unflinchingly portrays their descent into violence and desperation. Cassel’s portrayal of Marcus exemplifies the primal instinct for retribution, echoing the themes of masculinity and power explored in films like "A Clockwork Orange."

One of the most striking aspects of Irreversible is its unrelenting depiction of violence. The film is infamous for its explicit scenes, particularly the brutal rape sequence, which is shot in an unflinching, almost documentary-like style that strips away any cinematic glamour. This choice serves to provoke a visceral reaction, forcing viewers to confront the physical and psychological realities of violence head-on. The scene’s long take, which presents the assault in real time, shatters the audience's expectations of how such acts are typically portrayed in cinema, raising ethical questions about voyeurism and the depiction of suffering.

Beyond the graphic content, Irreversible is also a meditation on the themes of love and loss. The film invites viewers to reflect on the fragility of relationships and the profound impact of trauma not only on victims but also on their loved ones. The love story between Alex and Marcus is poignantly rendered in flashbacks, contrasting the intense passion they share with the horror that ultimately befalls them. This juxtaposition enhances the emotional weight of the narrative as viewers are left to grapple with the shattered remnants of what once was.

Noé’s innovative use of sound further amplifies the film's emotional intensity. The pulsating score and disorienting sound design mirror the chaotic emotional landscape of the characters. The soundscapes are often as unsettling as the visuals, creating an immersive experience that engulfs the audience in the story's chaos. The transition from moments of tranquility to overwhelming panic not only accentuates the horror of the film’s events but also leaves viewers feeling emotionally rattled and mentally engaged.

As the narrative unfolds in reverse, the film moves toward a sense of inevitability. Viewers witness the devastating consequences of the characters’ actions, culminating in a chilling understanding of how one moment can irreversibly alter the course of many lives. This exploration of fate and consequence echoes the moral ambiguities presented in "A Clockwork Orange," where the cyclical nature of violence and retribution raises profound ethical considerations about the cost of vengeance and the nature of humanity.

In conclusion, Irreversible is a daring and challenging film that confronts viewers with the darkest aspects of human experience. Its innovative narrative structure, graphic content, and emotional depth combine to create a powerful commentary on time, violence, and the fragility of love. In portraying the irreversible nature of trauma and the echoes of suffering, Noé crafts a film that remains etched in the minds of its audience, compelling them to reflect on the moral complexities of human behavior. Like "A Clockwork Orange," Irreversible forces audiences to grapple with their values and perceptions of morality, delivering a profound, if unsettling, cinematic experience.

7. Trainspotting (1996)

Trainspotting, directed by Danny Boyle and based on the novel by Irvine Welsh, is a groundbreaking film that delves into the chaotic lives of a group of heroin addicts living in Edinburgh. Renowned for its unflinching portrayal of addiction and its effects on youth culture, the film balances dark humor with moments of harrowing reality, creating an indelible commentary on the allure and consequences of drug use.

At the center of the narrative is Mark Renton, brilliantly portrayed by Ewan McGregor, who serves as both the film’s anti-hero and its moral compass. Renton’s struggle with addiction is depicted with raw authenticity, as the film explores not just the physical dependency on drugs but also the emotional and psychological toll it takes on him and his friends. The opening scene, with Renton’s voiceover reciting the famous line, “Choose life,” captures the film’s essence—an existential contemplation of a life spent in pursuit of fleeting highs against the backdrop of mundane despair.

The film’s vibrant visual style is complemented by an eclectic soundtrack that encapsulates the energy of the 1990s, featuring tracks from artists like Iggy Pop and Underworld. This musical score not only enhances the emotional resonance of key scenes but also reflects the youthful rebellion and subculture of the era. The iconic sequence set to Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life,” where Renton and his friends engage in drug use, encapsulates the euphoric highs and chaotic lows of addiction, contrasting the thrill of their lifestyle with the inevitable repercussions.

Trainspotting doesn't shy away from the harsh realities of addiction, portraying the physical degradation and moral decay that accompany it. The harrowing sequence where Renton descends into a toilet to retrieve a suppository highlights the lengths to which addicts will go to feed their habits. This moment serves as a brutally honest metaphor for the depths of addiction, pushing viewers to confront the grotesque side of substance abuse rather than romanticizing it. By depicting such visceral imagery, the film challenges societal perceptions of drug culture, prompting audiences to reflect on the human cost of addiction.

The relationships among the main characters—Renton, Spud (Ewen Bremner), Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), Begbie (Robert Carlyle), and Diane (Kelly Macdonald)—further enrich the narrative. Each character embodies different aspects of addiction and the various coping mechanisms employed to navigate their bleak lives. For instance, Spud represents the innocent yet tragically naive side of addiction, providing moments of humor and heart, while Begbie epitomizes the destructive nature of substance abuse and violence. His volatile personality introduces an element of danger that permeates the film, illustrating how addiction can breed unpredictable and violent behavior.

Moreover, Trainspotting serves as a poignant examination of escape and reality. The film captures the desire of its characters to escape the constraints of their environment and the banalities of life in working-class Edinburgh. Renton’s intermittent attempts to “choose life” reflect a deeper yearning for redemption and a return to normalcy, making his ultimate decisions throughout the film even more impactful. The juxtaposition of their drug-fueled escapism with the harsher realities they face after awakening creates a powerful commentary on the illusion of freedom that addiction offers.

Toward the film's conclusion, Renton's journey evolves from one of indulgence to a yearning for liberation from his addiction. The moment he ultimately decides to take a stand symbolizes a turning point, both for him and for the narrative as a whole. As he chooses to betray his friends to reclaim his life, it becomes clear that his escape from addiction comes at the cost of his past relationships, emphasizing the painful sacrifices often required for recovery.

In summary, Trainspotting is not just a film about drug addiction; it is a multifaceted exploration of identity, friendship, and the struggle for redemption against the backdrop of a grim reality. Its innovative storytelling, vibrant visuals, and impactful performances make it a landmark film that resonates with audiences long after the credits roll. Like "A Clockwork Orange," it compels viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about society and human behavior, serving as both a cautionary tale and a profound exploration of the highs and lows of life. As such, Trainspotting remains an essential cinematic experience, provoking deep thought about addiction, choice, and the desire for a better life.

8. Brazil (1985)

Brazil, directed by Terry Gilliam, is an extraordinary piece of cinematic art that merges dystopian themes with dark humor and surrealism. Set in a retro-futuristic world characterized by bureaucratic absurdity and oppressive government control, the film presents a satirical take on totalitarianism and the dehumanizing aspects of modern society. Through a captivating blend of striking visuals, inventive storytelling, and profound philosophical themes, Brazil remains a timeless commentary on the absurdities of bureaucracy and the struggle for individuality.

The film follows Sam Lowry, portrayed by Jonathan Pryce, a low-level government employee who dreams of escaping the mundane and oppressive world around him. Sam's life is dictated by an intricate bureaucratic system, where even the simplest tasks are mired in red tape and absurd regulations. The film opens with a darkly comic sequence in which a simple typo leads to the wrongful arrest of an innocent man, setting the tone for a world that prioritizes protocol over human compassion. This opening establishes the central motif of the absurdity of bureaucracy, with each character caught in a labyrinth of nonsensical procedures that strip away their humanity.

What sets Brazil apart is its unique visual style, which draws heavily from retro aesthetics and surrealist elements. Gilliam's masterful use of practical effects, elaborate set designs, and imaginative prop work create a hauntingly beautiful landscape that feels both familiar and alien. The blend of industrial architecture and dreamlike sequences, such as Sam's recurring visions of a winged woman, enhances the film's exploration of escapism and the longing for freedom. The chaotic visuals work in tandem with the narrative, underlining the paradox of a society that appears advanced yet is riddled with inefficiency and oppression.

Thematically, Brazil interrogates concepts of identity, memory, and the human desire for connection. Sam's daydreams of heroism and love manifest as he seeks a connection with the enigmatic Jill Layton, played by Kim Greist. Their romance stands in stark contrast to the cold world around them. As Sam navigates his oppressive environment, he grapples with the realities of love and the impact of societal structures on personal relationships. This exploration of love amid chaos is not just romantic; it serves as a critique of how bureaucratic systems can suffocate genuine human experiences.

The film’s intricate plot takes a darker turn as Sam becomes embroiled in a conspiracy involving the government’s brutal response to perceived dissent. As he attempts to navigate this treacherous world, he finds himself questioning his perceptions of reality. The introduction of the character of Mr. Kurtzmann, portrayed by Ian Holm, provides a chilling representation of the bureaucratic mindset—delivering orders without empathy or moral consideration. Kurtzmann’s character embodies the disconnection and moral decay that stems from an unfeeling system, reinforcing the film's critique of blind obedience to authority.

Gilliam does not shy away from existential themes, particularly the exploration of freedom and individuality against oppressive forces. Sam’s desperate attempts to reclaim his autonomy culminate in a series of increasingly surreal events, culminating in a nightmarish conclusion that leaves audiences questioning not just Sam's fate but the nature of reality itself. The film's infamous final sequence, where Sam is trapped within the very system he seeks to escape, underscores the futility of rebellion within a dehumanizing bureaucracy—a reflection on the cyclical nature of oppression.

Brazil also employs humor to enhance its critical perspective. The film's dark comedy emerges from its absurd situations, deadpan bureaucracy, and outlandish characters, creating a juxtaposition that both entertains and enlightens. For instance, the depiction of government agents as bumbling yet menacing reinforces the absurdity of the bureaucratic state, encouraging audiences to reflect on the ridiculousness of systems that prioritize control over humanity.

In summary, Brazil is an audacious exploration of a dystopian society that deftly intertwines elements of dark humor, surrealism, and social commentary. Through its striking visuals and complex narrative, the film serves as a powerful critique of bureaucracy, oppression, and the struggle for individuality in the face of a dehumanizing system. Similar to "A Clockwork Orange," it challenges viewers to reflect on their own lives and societal structures, asking profound questions about freedom, identity, and the human condition. As such, Brazil remains a landmark piece of cinema that resonates with audiences, offering a blend of artistry and critique that continues to provoke thought and discussion.

9. Taxi Driver (1976)

Taxi Driver, directed by Martin Scorsese, stands as a seminal work in American cinema, offering a raw and unflinching examination of urban alienation, isolation, and the descent into violence. The film follows Travis Bickle, portrayed hauntingly by Robert De Niro, a mentally unstable Vietnam War veteran who becomes increasingly disillusioned with the degrading social landscape of New York City in the 1970s. Through Travis’s eyes, viewers are immersed in a narrative that explores the psychological wounds of war and the impact of societal neglect.

Travis's character is deeply-faceted and profoundly tragic. His role as a taxi driver serves as a metaphor for his oversight of the city—he experiences the hustle and grime of urban life but remains detached from it. De Niro’s iconic line, “You talking to me?” captured in a memorable mirror scene, epitomizes Travis's internal conflict and growing alienation. In this moment, he rehearses the persona of a vigilante, foreshadowing his later descent into violence and isolation. His struggle with insomnia and hallucinations vividly illustrates his deteriorating mental state, where the chaotic city becomes a reflection of his fractured psyche.

The film’s depiction of 1970s New York City is integral to its narrative. Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Chapman create a grim and gritty atmosphere that encapsulates the societal decay of the era, marked by crime, poverty, and moral ambiguity. The setting itself is a living character, filled with neon lights, grimy streets, and the pervasive sense of danger that envelops Travis. The powerful imagery throughout the film serves to highlight the disconnection felt by both Travis and the people of the city, as individuals grapple with their restless lives amid an uncaring urban environment.

As the film progresses, Travis’s growing frustration with societal decay manifests in violent fantasies and a warped sense of justice. The character identifies with symbols of empowerment as he becomes increasingly infatuated with Pauline (Cybill Shepherd), a campaign worker he believes embodies the innocence and idealism that he so desperately craves. However, Travis’s obsessive behavior leads to a dangerous fixation, culminating in a misguided attempt to “save” her from the political corruption he perceives. This deep-seated need for connection is juxtaposed with his violent inclinations, creating an emotionally charged narrative rich in psychological complexity.

The film tackles themes of vigilantism and morality, exploring the thin line between heroism and madness. Travis's journey culminates in a climactic violent confrontation, where he attempts to save a young prostitute named Iris (Jodie Foster) from her oppressive circumstances, presenting him as both an anti-hero and a deeply flawed character. The moral ambiguity of his actions raises critical questions about the ethics of vigilantism and the desperate measures one might take when feeling powerless and isolated.

Scorsese’s use of music also enhances the film’s emotional weight, with Bernard Herrmann's haunting score interspersed throughout critical moments of the story. The soundtrack underscores the film’s tension and enhances the viewer's emotional response, making the experience all the more visceral. The use of jazz elements sets a mood that encapsulates loneliness and despair, mirroring Travis's internal struggles as he navigates his turbulent world.

Finally, Taxi Driver provides a compelling commentary on masculinity and societal expectations. Travis’s struggle for identity as a man in a rapidly changing world reflects broader cultural anxieties of the time. His violent outbursts can be seen as a misguided response to feelings of impotence and confusion, highlighting the film’s critique of traditional masculine ideals and the dangers of toxic masculinity.

In conclusion, Taxi Driver is a haunting and powerful exploration of alienation, violence, and longing for connection. Through masterful direction, evocative cinematography, and a haunting performance from De Niro, the film delves into the psyche of a troubled individual confronting a world filled with chaos and indifference. Much like films such as "A Clockwork Orange," it challenges viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about society, human behavior, and the profound effects of isolation. Taxi Driver remains a timeless classic that continues to resonate as it captures the dark undercurrents of urban life and the human condition, provoking thought and discussion about the nature of violence and the quest for identity in a fragmented world.

10. Fight Club (1999)

Fight Club, directed by David Fincher and based on the novel by Chuck Palahniuk, is a groundbreaking film that critiques consumer culture, explores themes of identity, and examines the psychological depths of masculinity in contemporary society. Through the story of an unnamed protagonist, portrayed by Edward Norton, the film delves into the alienation felt by modern individuals within a consumer-driven world that prioritizes materialism over genuine human connections.

The narrative centers on the disillusioned narrator, who lives a monotonous life filled with emptiness and dissatisfaction. His insomnia and existential angst reflect a society where individuals often feel trapped in the pursuit of unattainable ideals, leading him to seek an escape through consumerism. The iconic scenes of him attending support groups for various ailments demonstrate his desperate need for authentic human connection, even if he must fabricate identities to do so. This introduction to his character emphasizes the emotional disconnection prevalent in modern life.

The arrival of Tyler Durden, played by Brad Pitt, acts as a catalyst for the narrator's transformation. Tyler represents the antithesis of the shallow consumer culture, embodying chaos, rebellion, and a liberating yet destructive philosophy. Their dynamic relationship serves as a critical commentary on the duality of human nature—the innate desire for freedom clashing with societal expectations. As Tyler encourages the narrator to embrace his primal instincts, the film explores the seductive allure of anarchism and the reaction against conformity. The establishment of Fight Club as an underground society of men seeking empowerment through bare-knuckle fighting symbolizes a rebellion against societal constraints and a reclaiming of agency.

Fight Club boldly critiques consumerism and the consequences of a materialistic society. The famous line, “The things you own end up owning you,” encapsulates the film's central thesis: the realization that in the quest for material possessions, individuals often lose their sense of self. The film effectively employs dark humor to expose the absurdity of corporate branding and societal expectations, illustrated through scenes such as the narrator's disillusionment while attending a series of boring corporate meetings. The surreal marketing pitches serve to amplify the critique of how culture commodifies identity, revealing the hollow nature of modern consumer life.

The film's social commentary extends to themes of masculinity and identity, particularly through the character of Marla Singer, portrayed by Helena Bonham Carter. Marla embodies the chaos in the narrator's life; she disrupts his search for solace in the support groups and ultimately becomes a love interest. Her presence challenges conventional notions of femininity and serves as a reflection of the narrator's internal struggle. The dynamics of their relationship reveal the complexities of intimacy and connection, emphasizing the isolation and confusion often experienced in modern relationships.

Visually, Fight Club employs inventive cinematography and editing techniques that immerse the audience in the chaotic mind of the narrator. The use of split-screen effects, abrupt transitions, and intentional graininess contribute to the film's signature style, capturing the disarray of the protagonist's mental state. Additionally, the striking imagery employed in key sequences—such as the graphic depiction of the Fight Club underground fights—intensifies the visceral experience, compelling viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about violence and liberation.

As the narrative progresses, the tone shifts dramatically as Tyler's ideology becomes more radical. What begins as a countercultural escape transforms into an anarchistic group—Project Mayhem—that seeks to disrupt society on a larger scale. This evolution illustrates the unintended consequences of seeking freedom through destruction, challenging the morality of vigilantism. The narrator's conflict with Tyler escalates as he grapples with the ramifications of their actions, leading to a profound self-realization. The pivotal twist in the film reveals that Tyler is, in fact, a manifestation of the narrator's fractured psyche, symbolizing the internal struggle between societal conformity and the desire for self-actualization.

In the gripping conclusion, the narrator confronts his alter ego in a cathartic and violent climax, ultimately taking control of his identity. The final scenes, which feature the narrator's acceptance of both his darker and lighter sides, serve as a powerful resolution to the moral complexities presented throughout the film. As the credits roll to the sound of “Where Is My Mind?” by the Pixies, viewers are left to reflect on the repercussions of consumer culture and the quest for authentic identity.

In summary, Fight Club is a provocative exploration of modern societal issues, including consumerism, identity, and masculinity. Through its complex characters, dark humor, and striking visual style, the film invites audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about their own lives and the world around them. Much like "A Clockwork Orange," it challenges conventional norms, provoking discussion about individual existence in a society that often prioritizes conformity over authenticity. Fight Club remains an enduring classic, resonating with audiences and sparking critical reflections on the nature of self and the complexities of human existence.

11. Man Bites Dog (1992)

Man Bites Dog, directed by Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel, and Benoît Poelvoorde, is a provocative mockumentary that delves into the chilling psyche of a serial killer while simultaneously offering a scathing critique of media sensationalism and the desensitization of society towards violence. This Belgian film stands out for its audacious blending of dark comedy with gruesome realism, inviting viewers to reflect on the moral implications of media representation and the voyeuristic tendencies of audiences.

The narrative follows a film crew who document the life of Ben, played by Benoît Poelvoorde, a charismatic yet ruthless serial killer. Initially charming and articulate, Ben presents himself as a witty and engaging subject, captivating both the crew and the audience. However, as the film progresses, his sadistic nature becomes increasingly apparent, leading to a stark juxtaposition between his entertaining persona and the horrific acts he commits. This duality effectively draws viewers into a moral quandary, raising questions about complicity and the ethics of watching violence unfold.

The use of a documentary format heightens the impact of the film’s social commentary. The filmmakers deftly employ handheld camerawork, creating a sense of intimacy and immediacy that places the audience directly amid Ben’s chilling world. The camera becomes an inadvertent accomplice to the violence, reflecting the way the media often sensationalizes crime and violence for entertainment. By breaking the fourth wall and capturing the crew's reactions to Ben’s brutality, the film challenges audiences to examine their response to the portrayal of violence on screen.

One of the film’s most unsettling aspects is its exploration of the psychological toll of violence, both on the perpetrator and on those who witness it. Ben’s chilling nonchalance as he recounts his murders reveals a disturbing lack of empathy, serving to construct a portrait of a sociopathic mind. His interactions with the crew, particularly when he shifts from charming to menacing, emphasize the seductive allure of his character and the danger inherent in glorifying violent figures in popular culture. As he drags them deeper into his world, the crew's initial fascination gradually morphs into discomfort and complicity, culminating in a moral crisis that mirrors audience members' potential reactions to violent media.

Additionally, Man Bites Dog critiques the role of the media in sensationalizing crime and the public’s insatiable appetite for violence as entertainment. The film cleverly satirizes how news outlets often go to great lengths to capture shocking content, highlighting the ethical dilemmas involved in prioritizing ratings over integrity. The crew’s eagerness to document increasingly horrific acts for their film parallels the tendencies of mainstream media, which frequently exploits tragedy for sensational headlines. This biting satire prompts viewers to confront their consumption of media and the potential desensitization that results from a constant barrage of violence.

The film’s shocking conclusion serves as a powerful indictment of both its characters and the audience. As the story escalates to a brutal climax, the filmmakers challenge viewers' complicity in Ben's actions. The final scenes, where the crew's fascination turns into a nightmarish reality, force the audience to confront the moral implications of their voyeurism. Instead of providing catharsis, the film culminates in chaos, leaving viewers unsettled and questioning their ethical stance regarding violence in media.

Man Bites Dog is not just a meditation on violence; it is a profound commentary on society’s complex relationship with media representations of crime. Its dark humor and satirical critique of the film industry create a thought-provoking narrative that resonates well beyond its runtime. By engaging in a deeply disturbing yet captivating portrayal of a murderer, the film compels audiences to examine their values and the often troubling connections between consumption, violence, and morality.

In summary, Man Bites Dog remains a groundbreaking work that challenges viewers to reflect on the nature of violence and media representation. With its innovative storytelling, stark performances, and thought-provoking themes, it serves as a powerful reminder of the ethical responsibilities that accompany portraying brutality on screen. Like "A Clockwork Orange," it forces audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about their complicity in the narratives of violence that permeate modern life, making it an essential film for those seeking to understand the darker undercurrents of human behavior and media consumption.

12. Natural Born Killers (1994)

Natural Born Killers, directed by Oliver Stone and based on a screenplay by Quentin Tarantino, is a provocative satirical film that critiques the media's obsession with violence and the cult of celebrity surrounding criminals. Through its hyper-stylized visuals, frenetic editing, and sharp social commentary, the film explores themes of love, media manipulation, and the moral implications of sensationalism in contemporary society.

The narrative follows Mickey and Mallory Knox, played by Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis, two lovers on a murderous spree across America. Their bank-robbing and killing exploits are framed as a kind of modern-day Bonnie and Clyde, presenting a romanticized view of their violent journey. However, this glorification quickly crashes against the film’s harsh critique of society’s fascination with violence. The audience is invited to grapple with their feelings towards Mickey and Mallory, who embody both attraction and horror, highlighting the complexity of empathy for individuals steeped in depravity.

The film’s frenzied visual style is one of its most striking features, employing rapid cuts, unconventional framing, and vibrant colors to create a surreal and disorienting experience. Stone’s artistic choices reflect the chaotic mental states of the protagonists while simultaneously mimicking the sensationalized imagery often found in media coverage of crime. This stylistic approach complicates the viewer’s relationship with violence—what might appear thrilling on-screen raises unsettling questions about the real-world implications and consequences of such portrayals.

One of the film’s pivotal moments includes the portrayal of a fictionalized TV host, played by Robert Downey Jr., who embodies the media’s complicity in glorifying violence and perpetuating celebrity culture. His character, a sensationalist news anchor, exemplifies how the media sensationalizes and monetizes crime, contrasting sharply with the reality of the victims affected by Mickey and Mallory's actions. This meta-commentary highlights the moral abyss in which the media operates, perpetuating a cycle that transforms brutal killers into pop culture icons.

Natural Born Killers also critiques the moral ambiguity of its characters. Throughout the film, Mickey and Mallory are depicted not only as criminals but also as victims of a broken society. Scenes that delve into their traumatic backgrounds reveal the psychological wounds that contribute to their violent tendencies. This portrayal complicates the narrative, prompting audiences to consider the socio-economic factors and systemic issues leading to such violence. The film challenges viewers to contemplate the fine line between victim and perpetrator, ultimately questioning what drives individuals to commit violent acts.

The film’s conclusion reinforces its central message about the destructive nature of media sensationalism. As Mickey and Mallory become media legends amidst their violent exploits, the film reveals the chilling consequences of a society that glorifies violence. Their perceived liberation becomes an ironic twist, as the deluge of attention surrounding their deeds leads to a loss of autonomy and identity. The film’s final scenes serve as a haunting reminder of how society consumes violence for entertainment, all the while overlooking the real human cost behind such narratives.

The soundtrack of Natural Born Killers serves as another critical element that enhances its themes. With an eclectic mix of songs ranging from rock to classical, the music underscores the chaotic nature of the story and complements its satirical tone. For example, the use of Leonard Cohen's haunting "Waiting for the Miracle" underscores the film's exploration of longing and despair within the chaos of violence. The careful curation of music not only amplifies the emotional impact of key scenes but also reinforces the film's critique of how violence is intertwined with popular culture.

In conclusion, Natural Born Killers is a bold and thought-provoking film that serves as a scathing critique of the media's relationship with violence and the cult of personality surrounding criminals. Through its innovative visual style, complex characters, and powerful themes, the film compels viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about society's fascination with brutality. Much like "A Clockwork Orange," it challenges audiences to reflect on their consumption of media and the moral implications of glorifying violence. As such, Natural Born Killers remains a vital piece of cinema that resonates with contemporary discussions about love, violence, and the role of media in shaping societal narratives.

13. Pulp Fiction (1994)

Pulp Fiction, directed by Quentin Tarantino, is a groundbreaking film that revitalized the independent cinema movement of the 1990s and ultimately transformed the landscape of American filmmaking. Known for its eclectic storytelling, razor-sharp dialogue, and non-linear narrative structure, the film weaves together multiple storylines involving crime, violence, and redemption in a style that is both stylistically innovative and thematically profound.

The film is a tapestry of interrelated characters, including hitmen Vincent Vega (John Travolta) and Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson), mob boss Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames), and the intertwined lives of the characters surrounding them. One of the most striking elements of Pulp Fiction is the way it juxtaposes brutal violence with mundane conversations, emphasizing the absurdity of life within the criminal underworld. The infamous scene between Vincent and Jules, as they discuss the philosophical implications of a breakfast order—a seemingly trivial conversation about whether to call a burger a "quarter pounder" in France—, highlights Tarantino's ability to blend the philosophical with the profane, making relationships and dialogue both rich and layered.

A pivotal moment is the iconic scene in which Jules delivers his "Ezekiel 25:17" monologue before executing an unsuspecting man. The way Tarantino captures this moment combines tension with profound moral ambiguity, prompting audiences to reflect on the nature of fate and free will. The use of biblical references serves to elevate a brutal act into a moment of contemplation, illustrating how Tarantino explores the nuances of morality throughout the film. The audience is left questioning both the justification for violence and the characters' interpretations of morality.

Another standout character is Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman), whose captivating presence transforms the narrative's energy. Mia's iconic dance at Jack Rabbit Slim's diner, alongside Vince, exemplifies the film's mastery of blending style with substance. The scene is both a homage to classic cinema and a representation of their reckless lives, capturing the intoxicating nature of their world. This moment not only serves as a pivotal plot point in their relationship but also reinforces the interplay between danger and allure that permeates the film.

Pulp Fiction also explores themes of redemption and transformation as it navigates through moments of violence intertwined with surprising acts of humanity. The character of Butch Coolidge (Bruce Willis), a boxer who double-crosses Marsellus Wallace, reflects this complexity. His journey toward personal redemption is highlighted by his decision to return home to rescue his girlfriend, Fabienne (Maria de Medeiros), despite the chaos surrounding him. Butch's ultimate showdown with Marsellus, which culminates in a twist of fate as they find themselves captured and face their fears, challenges the audience's perception of heroism and villainy.

Tarantino's distinctive use of music further elevates the narrative, as the carefully curated soundtrack enhances the film's mood and character development. Iconic tracks like "Girl, You'll Be a Woman Soon" by Urge Overkill play during key scenes, masterfully combining the characters’ emotional journeys with the visceral world they inhabit. The music selection is not merely an accompaniment; it enriches the narrative, solidifying moments of intensity and nostalgia.

The film's non-linear storytelling structure demands active engagement from the audience as it dissects traditional narrative forms. By presenting events out of chronological order, Tarantino invites viewers to piece together the storyline themselves, creating a sense of intrigue and investment. The way the film jumps between storylines—such as moving from Vincent and Jules to Butch's arc—serves to underline the interconnectedness of their lives, reflecting the chaos of the underworld they inhabit.

In conclusion, Pulp Fiction remains a landmark film that captures the multifaceted nature of life, love, and violence within a stylized framework that blends drama, humor, and philosophy. Its unforgettable characters, sharp dialogue, and innovative structure set a new standard for storytelling in cinema. Like "A Clockwork Orange," it challenges viewers to confront complex moral questions, and this combination of themes continues to resonate. With its enduring influence on filmmakers and audiences alike, Pulp Fiction is not just a film; it is a cultural phenomenon that invites ongoing reflection and discussion about the layers of human experience within a chaotic world.

14. Joker (2019)

Joker, directed by Todd Phillips, presents a chilling and thought-provoking origin story for one of the most iconic villains in popular culture. This character study centers on Arthur Fleck, portrayed masterfully by Joaquin Phoenix, a struggling stand-up comedian grappling with a debilitating mental illness and overwhelming societal rejection. The film serves as a powerful critique of social injustice, mental health stigma, and the effects of neglect within a fractured society.

Set in a gritty, decaying Gotham City during the 1980s, Joker paints a portrait of urban despair and isolation. The film captures a sense of hopelessness as Arthur navigates a world that seems determined to break him. Everyday scenes depict his struggles—ranging from his humiliating job as a clown to his complicated relationship with his mother, Penny (Frances Conroy). The atmosphere is suffocating, with the cinematography featuring heavy shadows and dull colors, enhancing the feeling of Arthur's internal and external struggles. This visual choice highlights Gotham as not just a backdrop but a character in its own right, one that exacerbates Arthur's plight.

Arthur's descent into madness is marked by a profound sense of alienation. His aspiration to be a stand-up comedian becomes a painful reflection of his inability to connect with others. Scenes showcasing his awkward comedic performances reveal his deep-seated insecurities and longing for acceptance. The film effectively juxtaposes these moments with Arthur's violent outbursts, highlighting the transformation of his pain into rage. This transformation raises crucial questions about the catalysts of violence in society and the fragile line between victim and perpetrator.

Joaquin Phoenix's performance is nothing short of transformative, capturing the internal turmoil of a man pushed to the edge. His physicality, particularly his haunting laughter—a condition tied to his mental health—adds layers of complexity to his character. Phoenix's commitment to the role is evident in the visceral portrayal of Arthur’s breakdown, evoking empathy even as he spirals further into chaos. The iconic scene where Arthur dances in full Joker makeup after committing a violent act serves as both a celebration of his newfound identity and an unsettling commentary on the joy he finds in embracing his darker side.

A significant aspect of Joker is its exploration of mental health awareness and the societal failures surrounding it. Arthur’s struggles with mental illness and his desperate attempts to seek help from the city’s social services exemplify the lack of support systems for vulnerable individuals. The film critiques the neglect of mental health issues, emphasizing how societal apathy can contribute to tragic outcomes. An early scene where Arthur is denied his medication following funding cuts to mental health services compellingly illustrates this point, serving as a poignant reminder of the real-world implications of such systemic failures.

The character of Thomas Wayne, played by Brett Cullen, also plays a crucial role in shaping Arthur's narrative. As a symbol of privilege and power, Thomas embodies the societal elite who remain disconnected from the struggles faced by individuals like Arthur. The film raises questions about the moral responsibilities of those in power—particularly when Arthur perceives Wayne as a potential savior, only to confront the harsh reality of being dismissed by him. This interaction becomes a pivotal moment in Arthur's transformation into the Joker, reinforcing the theme of class disparity and the consequences of societal neglect.

The film’s score, composed by Hildur Guðnadóttir, adds another layer of emotional depth. The haunting orchestral music captures the mood of despair and impending chaos, enveloping viewers in Arthur’s psychological state. The score swells during critical moments, amplifying the tension and eliciting visceral reactions that resonate well beyond the screen. The music effectively intertwines with the narrative, reinforcing the themes of isolation and madness that permeate the film.

In its climax, Joker transcends the superhero genre to become a chilling socio-political commentary. Arthur’s emergence as the Joker becomes a symbol of rebellion against the societal structure that has oppressed him and countless others. The film’s conclusion—marked by chaos and violence—forces viewers to confront the uncomfortable truth of how society can create its monsters when individuals are left unheard and unseen.

In summary, Joker is a compelling examination of the complexity of identity, the impact of mental illness, and the societal forces that shape individuals into what they become. Through a stunning performance by Joaquin Phoenix, masterful direction by Todd Phillips, and a powerful social critique, the film evokes deep reflection on the interplay of societal neglect, violence, and the quest for validation. Much like "A Clockwork Orange," it challenges audiences to confront uncomfortable realities and question their perceptions of morality, agency, and the consequences of a society that often marginalizes its most vulnerable members. Joker ultimately stands as a significant cultural moment, provoking thought and discussion about empathy, justice, and the human condition.

15. No Country for Old Men (2007)

No Country for Old Men, directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, is a masterful adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's novel that deftly intertwines elements of suspense, morality, and the changing landscape of America. Set against the stark backdrop of West Texas in the 1980s, the film explores themes of fate, violence, and the consequences of choices in a world increasingly dominated by chaos and moral uncertainty.

The film follows three central characters whose lives become entangled after a drug deal gone wrong, which leads to the discovery of a briefcase full of cash. Llewellyn Moss, portrayed by Josh Brolin, stumbles upon this money while hunting antelope and, believing he has found a path to wealth, decides to take it. Moss’s seemingly simple choice propels him into a deadly game of cat and mouse with Anton Chigurh, played chillingly by Javier Bardem. Chigurh is a hitman who operates by his twisted code of ethics, using a coin toss to determine the fate of his victims. His portrayal as a relentless force of nature establishes him not just as a villain but as an embodiment of inevitability—an agent of fate that highlights the themes of chance and choice central to the film's narrative.

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, portrayed by Tommy Lee Jones, serves as the moral center of the story. As he investigates the ensuing violence, Bell reflects on the changing nature of crime and the erosion of traditional values. His introspective monologues reveal a man grappling with feelings of helplessness in the face of a world he no longer understands. Bell’s character poignantly illuminates the film’s central thesis: that the timeless struggle between good and evil has evolved, leaving him questioning his role in a society that seems to be increasingly indifferent to morality. His statement, “I don’t know what’s going on, but I do know that it’s bad,” encapsulates this sentiment, revealing his struggle to reconcile his belief in justice with the harsh realities of a violent world.

The cinematography by Roger Deakins is striking and enhances the film’s visual storytelling. The expansive landscapes of Texas serve as a haunting backdrop, accentuating the film's atmosphere of desolation. The Coen brothers utilize wide shots to capture the vastness of the land, emphasizing the characters’ isolation and the stark realities they face. The use of natural light creates a sense of authenticity, allowing the viewer to feel immersed in the relentless environment where survival depends on quick decisions and cold calculations.

A standout aspect of No Country for Old Men is its deliberate pacing, which builds tension through moments of silence and stillness. The absence of a traditional score during key scenes emphasizes the weight of impending violence. For instance, the chilling scene in which Chigurh confronts a gas station owner exemplifies this technique. The slow, methodical exchange between them suddenly turns violent, showcasing how Chigurh’s cold demeanor and lack of empathy can result in life-and-death decisions. This unpredictability keeps the audience on edge, forcing them to grapple with the senselessness of violence.

Irony permeates the film, particularly regarding the nature of justice and morality. Chigurh is a disturbingly rational character; his actions and reasoning contrast sharply with Bell's more empathetic worldview. This juxtaposition highlights the existential crisis of Bell as he types his report but reflects on the ungraspable nature of fate. The film invites viewers to consider how morality can become subjective, questioning the very essence of justice in a chaotic world where traditional values appear obsolete.

Moreover, the film's ending leaves a lasting impression, resonating with its central themes. After a series of violent confrontations, the story culminates in a somber realization of the inevitability of change. The final scene, in which Bell recounts a dream about his father to his wife, symbolizes his longing for the past—a time he perceives as simpler and more righteous. The dream is layered with meaning, representing a desire for connection and understanding in a world that has shifted beyond his comprehension. This ambivalence encapsulates the film's exploration of the fragility of morality in an ever-evolving society.

In summary, No Country for Old Men is a compelling meditation on fate, violence, and the moral complexities of contemporary society. Through the interplay of its multi-dimensional characters, striking cinematography, and haunting narrative structure, the film engages viewers in a profound reflection on the nature of choice and consequence. Like films such as "A Clockwork Orange," it challenges audiences to consider their understanding of right and wrong within a troubling reality, making it a significant work in the canon of American cinema. The Coen brothers’ bleak yet brilliant vision resonates strongly, leaving viewers to ponder the often harsh truths of existence in a changing world.

16. Hate (1995)

Hate (original title: La Haine), directed by Mathieu Kassovitz, is a provocative French film that incisively explores themes of social unrest, systemic inequality, and the cycle of violence in the aftermath of a riot in the Parisian suburbs. Released in 1995, the film is a poignant reflection of the social tensions faced by disenfranchised youth, serving as a powerful commentary on race relations, police brutality, and the struggles of marginalized communities in contemporary France.

The story unfolds over 24 hours and follows three friends—Vinz (Vincent Cassel), Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui), and Hubert (Hubert Koundé)—who navigate life in the volatile and impoverished environment of a housing project. Following the police shooting of their friend Abdel, the trio grapples with feelings of anger, hopelessness, and a burgeoning desire for retribution. The structure of the film, combining real-time storytelling with intense character development, immerses viewers in the emotional landscape of its protagonists while capturing the broader social issues at play.

Vinz serves as the film's most volatile character, channeling his anger and frustration into a quest for vengeance. His character embodies the raw energy of youth struggling against oppression but also highlights the destructive potential of that anger when left unchecked. This theme is poignantly encapsulated in the film's famous closing line: "Ça va être la merde" ("It's going to be hell"), which serves as a foreboding reminder of the disastrous consequences that often accompany such cycles of violence.

In contrast, Hubert emerges as the voice of reason among the trio. As a boxer with aspirations to escape the cycle of violence, he grapples with his frustrations while trying to steer his friends away from confrontation. Hubert's character illustrates the internal conflict faced by many young people in marginalized communities who wish to break free from their surroundings yet feel powerless against the overwhelming forces of societal oppression. His struggle for dignity and identity resonates deeply, as he endeavors to find meaning amidst chaos.

Hate also excels in its visual storytelling, employing stark black-and-white cinematography that accentuates the film's raw emotion and creates a gritty, realistic aesthetic. The choice to shoot in black and white not only serves as a stylistic representation of the bleakness of the characters' lives but also reflects the moral dichotomy of the societal issues they confront. Symbolic scenes, such as the early interactions with riot police and the harrowing moments of tension within their neighborhood, showcase the film's ability to blend artistic expression with social commentary effectively.

A standout moment occurs when Vinz finds a gun lost by a police officer during the riots, which becomes a poignant symbol of power and violence. This turning point in the film raises critical questions about the nature of authority and the lengths to which individuals will go to reclaim their agency. As the trio experiences escalating confrontations with police and engages in reckless behavior, the film lays bare the perilous allure of violence as a means of resistance.

Throughout the film, Kassovitz delivers a sharp critique of the media's portrayal of urban youth, reiterating the disconnect between representation and reality. News segments interspersed within the narrative serve to highlight how the actions of marginalized individuals are often sensationalized, fueling a cycle of hatred and misunderstanding. The film challenges viewers to reconsider their perceptions of these communities, dispelling stereotypes and humanizing the individuals behind the headlines.

The film's intense climax serves as a haunting reflection on the cyclical nature of violence. As the friends confront their realities, the film captures both the despair of their circumstances and the inevitability of conflict. The closing shots—filled with ambiguity and sorrow—underscore the grim realities faced by people living in these conditions, leaving audiences to ponder the broader implications of societal neglect and systemic failures.

In conclusion, Hate (La Haine) is a powerful, thought-provoking exploration of social unrest, identity, and the impact of systemic violence on disenfranchised youth. Through its compelling characters, striking visual style, and incisive social critique, the film serves as a timeless reminder of the complexities surrounding anger, belonging, and the human condition. By confronting the harsh realities of life in marginalized communities, Hate resonates strongly with discussions about social justice and inequality, making it a significant cinematic work that remains relevant in today's world. Like "A Clockwork Orange," it invites viewers to engage with uncomfortable social truths and reflect on how societal structures influence individual lives and choices.

17. Bronson (2008)

Bronson, directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, is a bold and stylistically audacious film that recounts the life of Michael Peterson, who later adopts the notorious name of Charles Bronson. Portrayed with fierce intensity by Tom Hardy, Bronson offers a gripping exploration of identity, violence, and the complex nature of fame within the confines of Britain's prison system.

The film is framed as a surreal, exaggerated memoir that delves into Bronson's life, beginning with his troubled childhood in Luton. Refn presents Bronson as a product of his environment—his propensity for violence is rooted in a chaotic upbringing marked by neglect and a desperate search for identity and recognition. This exploration of early influences sets the stage for understanding the psychological complexities of his character, making it clear that Bronson’s infamy is both a product of his actions and the media’s portrayal of him.

Hardy's performance is nothing short of extraordinary, encapsulating Bronson's volatile personality with a raw physicality and charisma that commands attention. From the moment he first appears on screen, Hardy immerses himself fully into the role, transforming his body to embody the violent delinquent. His commitment to character is reflected in scenes where he transitions from a calm demeanor to explosive aggression, revealing the duality of Bronson as both an artist and a brute. This complexity creates a layered character who is both fascinating and tragic, drawing viewers into his internal conflict and the desperate need for validation.

The film’s visual style is striking, employing a blend of stylized cinematography and theatrical elements that heighten the narrative's absurdity. Refn utilizes bold colors, unusual framing, and imaginative staging, particularly in the film’s dreamlike sequences where Bronson performs for an audience, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy. These moments emphasize his desire for attention and the performance aspect of violence, as Bronson often sees himself as a larger-than-life figure. The self-aware narrative serves to comment on the nature of fame, suggesting that Bronson’s notoriety is as much a product of spectacle as it is of his heinous acts.

One of the film's most distinctive features is its exploration of the penal system and the societal implications of incarceration. Bronson's repeated battles with authority and his manipulation of the prison system reflect resistance to control, showcasing how the institution’s failures contribute to cycles of violence. His time in solitary confinement becomes a canvas for his artistic expression, as he fills the space with drawings and performances that contradict the violence typically associated with prison life. This portrayal raises questions about the role of art in confronting despair and the human capacity for creativity even in the bleakest circumstances.

Bronson’s relationships with other inmates and authority figures further illustrate the complexities of his character. He forms a complicated bond with a fellow inmate, who becomes a symbol of both camaraderie and competition. Their dynamic reveals insight into Bronson’s inability to connect meaningfully with others, underscoring the isolation that defines his existence. Similarly, his interactions with prison guards highlight the paradox of his situation; while he seeks to dominate through fear and violence, this behavior often leads to further confinement and alienation.

The film culminates in a series of explosive encounters that illustrate Bronson's embrace of violence as a means of asserting control and identity. The climactic scenes, punctuated by heartbreak and aggression, reflect the tragic consequences of his choices. As Bronson solidifies his status as a cultural figure, it is clear that his fame is built upon a foundation of chaos and destruction, prompting viewers to question the societal fascination with violence.

In its conclusion, Bronson does not offer easy answers or a moral resolution. Instead, it presents Bronson as a complex figure trapped in a cycle of violence, challenging audiences to reconcile their perceptions of him with the underlying factors that shaped his identity. The film invites reflection on broader themes surrounding masculinity, authority, and the construction of self in a hostile world.

Bronson is a visceral and thought-provoking exploration of identity, violence, and the paradoxes inherent in the pursuit of fame. Through its compelling performances, striking visuals, and complex narrative, the film offers an unflinching look at the mind of one of Britain’s most notorious prisoners. Much like "A Clockwork Orange," it engages with uncomfortable truths about human nature, the impact of societal structures, and how individuals navigate their realities. Bronson remains an influential work, provoking ongoing examination of the relationship between violence, art, and identity, and the social dynamics that shape our understanding of both.

18. Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984)