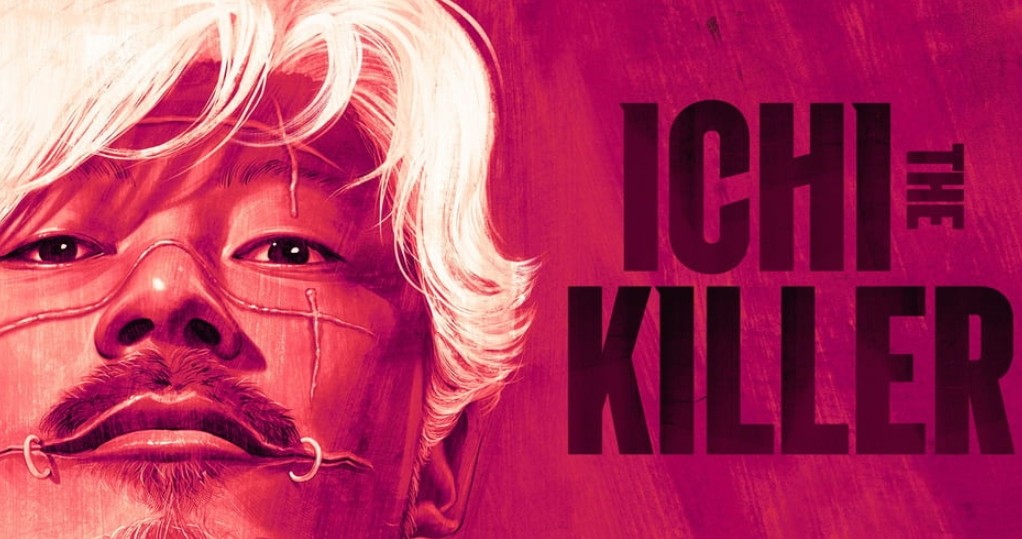

20 Thrilling Movies Like Ichi the Killer

Table Of Contents:

- 20 Thrilling Movies Like Ichi the Killer

- 1. Man Bites Dog (1992)

- 2. Irreversible (2002)

- 3. American Psycho (2000)

- 4. I Saw the Devil (2010)

- 5. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975)

- 6. Oldboy (2003)

- 7. Seven (1995)

- 8. Visitor Q (2001)

- 9. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)

- 10. The Chaser (2008)

- 11. Ichi (2003)

- 12. Gozu (2003)

- 13. Bronson (2008)

- 14. No Country for Old Men (2007)

- 15. Benny's Video (1992)

- 16. Audition (1999)

- 17. Scum (1979)

- 18. City of God (2002)

- 19. Dead or Alive (1999)

- 20. A History of Violence (2005)

If Ichi the Killer serves as Takashi Miike's shocking challenge to audiences, urging them to confront the darkest aspects of violence and morality, then the films that follow are similarly audacious explorations of the human psyche. This iconic 2001 film is infamous for its graphic brutality, spiraling psychological tension, and layered narratives, effectively raising the bar for disturbing cinema. However, numerous other movies unravel equally dark themes marked by obsession and shocking imagery, inviting viewers to delve deeper into the complexities of human nature. Here are 20 films that boldly traverse the boundaries of discomfort, thereby testing your resilience and expanding your cinematic horizons.

20 Thrilling Movies Like Ichi the Killer

1. Man Bites Dog (1992)

Director: Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel, and Benoît Poelvoorde

This striking Belgian film offers a darkly comedic look at the life of Ben, a charismatic yet utterly depraved serial killer, as he allows a film crew to document his crimes. The crew, initially fascinated by his charm and articulate nature, gradually becomes complicit in his atrocities as they trade morality for sensationalist entertainment. This provocative narrative raises pressing questions about the ethics of filmmaking, the voyeurism of audiences, and the consequences of glorifying violence.

Man Bites Dog serves as a meta-commentary on the media’s relationship with violence, cleverly blurring the line between documentary and fiction. As viewers follow Ben's increasingly gruesome exploits—ranging from robbery to murder—the film forces a confrontation with the unsettling reality of how society consumes violence. For instance, one memorable scene showcases the crew's growing desensitization as they film a murder from an extremely close angle, highlighting their moral decay.

The film employs a mockumentary style, akin to This Is Spinal Tap, yet it veers sharply into horror territory, creating an experience that is both comically absurd and deeply disturbing. The use of humorous dialogue juxtaposed against horrific acts prompts audiences to reflect on their own complicit enjoyment of violent media.

Notably, Man Bites Dog doesn’t shy away from exploring the psychology of its central character. Ben, portrayed masterfully by Poelvoorde, is not just a one-dimensional villain; his charm and passion for his work make him unsettlingly relatable, thus complicating the audience's response. This duality invites viewers to question what they find entertaining and the moral implications behind enjoying such content.

Released in the early 1990s, this film quickly gained notoriety for its controversial subject matter, becoming a cult classic that continues to resonate today. Its willingness to delve into the disturbing aspects of human behavior influenced a wave of films that followed, including Funny Games and American Psycho, which also tackled themes of violence and media consumption in provocative ways.

In a memorable scene that exemplifies the crew's moral degradation, Ben enlists the filmmakers to help him dispose of a victim's body, showcasing how the process of documenting violent acts becomes a perverse collaboration. This moment prompts audiences to reflect on their own fascination with brutality and the lengths to which people go for entertainment.

Man Bites Dog ultimately serves as a chilling reminder of the potential for glamorization of violence in media. Its dark humor and razor-sharp social commentary challenge viewers to consider the ethical ramifications of their entertainment choices, making it an essential film for anyone interested in the intersections of cinema, violence, and morality. The film not only entertains but also provokes meaningful discussion about the desensitization to violence that stems from its depiction in popular culture.

2. Irreversible (2002)

Director: Gaspar Noé

Irreversible is a visceral journey into the darker facets of human existence, told in a unique reverse chronological structure that examines the aftermath of a brutal crime. The film follows a man's desperate quest for vengeance after his girlfriend is brutally raped and murdered. The unconventional narrative style forces viewers to experience the harrowing night of violence in a disorienting manner—beginning with the devastating consequences and working backward to the events that led up to the tragedy. This structure not only heightens the emotional intensity but also evokes a sense of fatalism, as the audience is acutely aware of the impending horror that awaits.

The film is notorious for its graphic depictions of violence and sexual assault, particularly the lingering, almost unwatchable 10-minute rape scene, which has sparked intense debate regarding its necessity and ethical implications. Gaspar Noé employs unflinching realism to confront viewers with the brutality of the act, stripping away any glamorization of violence. This audacity compels audiences to grapple with their reactions, effectively shattering preconceived notions about cinematic representations of trauma.

Notably, the film’s use of sound plays a crucial role in amplifying its impact. The overwhelming audio, including an unsettling score that evokes a sense of dread, enhances the chaotic nature of the visual storytelling. This sonic landscape immerses viewers in the characters’ emotional turmoil, drawing them deeper into the narrative's nightmarish reality. The combination of intense visuals and sound design creates a relentless experience that lingers long after the credits roll.

Upon its release, Irreversible sparked substantial controversy, earning both praise and criticism for its uncompromising portrayal of violence and its existential themes. It challenged the boundaries of cinematic storytelling, influencing a wave of filmmakers interested in confronting uncomfortable truths. The film became a touchstone for discussions surrounding the ethics of representation in cinema and the responsibilities of filmmakers to their audiences.

The reversing narrative not only serves as a storytelling technique; it also invites viewers to consider the implications of their own voyeurism. By witnessing the aftermath of violence first, viewers experience a visceral form of empathy and horror as they confront the fragility of life and the irreversible consequences of actions. This approach enforces a profound reflection on time, fate, and the destructive potential of revenge.

In a poignant scene toward the end of the film, as the characters reflect on their relationships and seemingly mundane moments before the tragedy, viewers are reminded of life’s transient beauty. This juxtaposition of the ordinary with the horrific emphasizes the film’s existential commentary, converting the narrative into a meditation on suffering, loss, and the futility of seeking revenge.

Irreversible ultimately challenges viewers to confront the darkest corners of their own humanity. Beyond its shock value, it serves as a grim exploration of how violence irrevocably alters lives. Gaspar Noé’s arresting film is not merely an exercise in shocking audiences; rather, it is a profound commentary on the human condition that forces reflection on morality, time, and the reverberating effects of trauma. The film endures as a critical work that continues to provoke dialogue around the representation of violence in cinema, showcasing the need for thoughtful engagement with such intense themes.

3. American Psycho (2000)

Director: Mary Harron

American Psycho offers a satirical yet chilling portrayal of a wealthy Wall Street investment banker, Patrick Bateman, played by Christian Bale, who leads a double life as a psychopathic killer. Set in the 1980s, the film vividly captures the era's obsession with consumerism, materialism, and superficiality. As Bateman spirals deeper into violence and madness, the film critiques not only his character but also the larger societal framework that enables such depravity to thrive.

The film brilliantly contrasts Bateman's polished exterior with his inner turmoil and violent tendencies. One striking example is the meticulously curated lifestyle he maintains, complete with designer clothes, perfectly groomed looks, and a penchant for expensive dining. The juxtaposition of these high-society privileges against his heinous acts reinforces the film’s critique of the emptiness behind wealth and status. For instance, the scene where Bateman describes his morning routine in excruciating detail is both darkly humorous and grotesquely revealing, showcasing his obsession with appearances and control while foreshadowing his violent impulses.

Based on Bret Easton Ellis's controversial novel, American Psycho faced significant backlash for its graphic violence and portrayal of women. However, it also incited important conversations about masculinity, identity, and the moral vacuity of the corporate culture it satirized. The film’s release came at a time when the dot-com bubble was inflating, reflecting a society increasingly defined by wealth and status While some viewed it as misogynistic, others praised it for its dark humor and incisive social commentary.

One of the film's most memorable scenes involves Bateman's infamous "business card" showdown with his colleagues. The absurdity of their obsession with brand names and status symbols highlights the superficial values that permeate their lives. Bateman's reaction as he compares the cards serves to underscore his burgeoning psychopathy and envy—a harbinger of the violence to come. This pivotal moment encapsulates the film’s critique of a self-absorbed culture that prioritizes appearance over authenticity.

Christian Bale delivers a masterful performance that intricately balances charm and menace, compelling viewers to grapple with their responses to Bateman. Bale’s physical transformation for the role, which included intensive workouts to achieve a razor-sharp physique, mirrors Bateman's own obsession with control and perfection. The actor's ability to oscillate between charismatic and terrifying effectively draws audiences into Bateman's conflicted psyche. For example, the chilling calmness he exhibits during a murder scene contrasts sharply with his frenzied inner monologues, emphasizing the depth of his character’s madness.

The film employs a surreal, almost dreamlike quality throughout, particularly evident in scenes where Bateman's grip on reality begins to falter. Notable is the moment he converses with seemingly oblivious characters, raising questions about hallucination and truth. This surrealism culminates in a climactic sequence that leaves viewers questioning whether Bateman's actions are real or figments of his deranged mind.

American Psycho stands as a provocative exploration of identity, consumerism, and moral decay. Its blend of horror and dark comedy encourages critical reflection on the ethical implications of wealth and the nature of violence in modern society. Far from being merely a film about a serial killer, it challenges audiences to consider the societal constructs that foster such monstrous behavior. The lasting impact of American Psycho is evident in its continued relevance, prompting ongoing discussions about the intersection of capitalism, identity, and morality in contemporary culture. This film serves as both a thrilling ride into the mind of a disturbed individual and a biting critique of the society that creates him.

4. I Saw the Devil (2010)

Director: Kim Ji-woon

I Saw the Devil is a gripping South Korean thriller that intertwines revenge and moral complexity. The film follows Kim Soo-hyun, a secret agent portrayed by Lee Byung-hun, whose fiancée is brutally murdered by a sadistic serial killer named Jang Kyung-chul, played by Choi Min-sik. Instead of following the conventional path of seeking justice through the law, Soo-hyun embarks on a twisted quest for vengeance, inflicting gruesome torment upon his fiancée's killer. The narrative unfolds as a cat-and-mouse game, leading to an exploration of the psychological and emotional toll of revenge.

The film utilizes a cat-and-mouse dynamic that keeps viewers on the edge of their seats. Soo-hyun’s elaborate plans to track down Kyung-chul further emphasize the moral ambiguity inherent in his pursuit of vengeance. For instance, in a chilling scene, Soo-hyun captures Kyung-chul and tortures him in various ways, presenting a horrific spectacle that leads audiences to question the morality of his actions and the cycle of violence he perpetuates. This exploration of revenge blurs the line between hero and villain, making audiences wrestle with their empathy for Soo-hyun as he becomes increasingly methodical in his brutal actions.

The film is characterized by its striking visual style, with Kim Ji-woon employing creative camera angles and atmospheric lighting to enhance the emotional weight of each scene. The brutal yet beautiful cinematography captures both the horrific acts of violence and the haunting landscapes of South Korea, creating a visually arresting contrast. For instance, the juxtaposition of serene rural settings with horrific violence heightens the film’s tension and contributes to a sense of impending doom.

I Saw the Devil delves into the psychological ramifications of vengeance on both the avenger and the victim. The narrative frequently presents emotional flashbacks, allowing the audience insight into Soo-hyun’s internal struggle and the weight of his grief. This character development transforms him from a grieving fiancé into a figure consumed by his thirst for vengeance, forcing viewers to consider the soul’s deterioration in the pursuit of retribution. After multiple encounters, the emotional toll on both characters creates a poignant examination of the human psyche and the aftermath of violence.

The film engages with broader socio-cultural themes, reflecting on the societal fixation with violence and justice in South Korea. It critiques the failings of the legal system by presenting Soo-hyun’s perspective as a direct commentary on the idea that justice is often unattainable through conventional means. As the film progresses, it becomes less a story of avenging a loved one and more a critique of the cycle of violence that ensues when individuals resort to their own form of justice.

I Saw the Devil garnered critical acclaim for its audacious approach to the thriller genre, quickly earning a reputation as one of the most provocative films of the 2010s. The film's visceral storytelling and moral ambiguity invite ongoing discussions about the nature of violence and the consequences of revenge. It challenges audiences to reflect on their perceptions of justice and the human capacity for brutality, making it a compelling watch for those interested in films that push the boundaries of conventional narratives.

With its blend of relentless action, psychological depth, and moral questioning, I Saw the Devil solidifies its place as an unforgettable entry in the revenge thriller genre. It stands as both an exhilarating film experience and a poignant cautionary tale about the perils of vengeance. The film urges viewers to contemplate the fine line between justice and retribution and ultimately leaves them questioning the true cost of revenge—a theme as relevant today as the film’s release. Through its haunting narrative and powerful performances, I Saw the Devil remains an essential study of the darkness that resides within us all.

5. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975)

Director: Pier Paolo Pasolini

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is a harrowing adaptation of the Marquis de Sade’s infamous novel, transposed to the context of World War II Italy under fascist rule. The film depicts a group of wealthy, powerful men who, in a secluded villa, subject a group of young boys and girls to horrific acts of sexual liberation and sadistic pleasure. Structured in four segments—The Anus of the World, The Circle of Death, The Circle of Blood, and The Circle of Shame—it emphasizes themes of power, dehumanization, and the impact of socioeconomic structures on human morality.

This film achieves an unsettling juxtaposition between the insatiable cruelty of the ruling elite and the innocence of the victims. It deliberately positions viewers to confront their own moral boundaries as it depicts unflinching scenes of depravity. One particularly shocking sequence features enforced participation in grotesque acts, causing audiences to grapple with the stark power dynamics at play. The sheer graphic intensity serves as both a critique of fascism and a wider condemnation of the moral bankruptcy inherent in absolute power.

Pasolini employs a stark and clinical aesthetic, contrasting the brutal subject matter with a stylized visual approach that elicits both horror and fascination. The cold, sterile cinematography strips the scenes of warmth, reinforcing the film’s themes of alienation and dehumanization. For example, the use of static shots and minimal camera movement compels viewers to confront the lingering horror rather than escape it. The film's composition, often reminiscent of classical painting, heightens its visceral impact, forcing audiences to reckon with the horrific beauty of the imagery.

Salò is not merely a tale of hedonism and violence; it functions as a biting critique of the ways in which power exploits and corrupts. The characters embody archetypes of a fascist society—cruelty masked as civility, the embodiment of authority wielded in contempt of personal freedoms. For example, the “Duke” character represents an archetype of authoritarian control, drawing parallels between the film's events and the broader historical context of fascism, totalitarian regimes, and their violent oppression of individuality and dissent.

Upon its release, Salò met with intense controversy and censorship, often regarded as one of the most disturbing films ever made. Critics and audiences alike were polarized, facing visceral reactions to its content. Yet, over time, the film has been re-evaluated as a crucial work of political cinema, instigating dialogues about freedom, oppressiveness, and the nature of evil. The film’s notoriety spurred important conversations about artistic expression, the limits of decency in art, and the consequences of social and political oppression.

One of the film's most profound themes is the relationship between pleasure and pain, evoking the sadistic nature of power dynamics. The characters' grotesque indulgences lead to their ultimate moral decay, blurring the lines between victimization and complicity. As the story unfolds, the sexual violence depicted is interwoven with ritualistic elements, making Salò not merely shocking but intellectually probing, forcing viewers to consider the ethics of desire and the capacity for human depravity.

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom remains an unparalleled exploration of the darkest corners of human nature, an unflinching examination of how power corrupts and degrades morality. Its controversial content serves as a catalyst for critical thought, challenging viewers to confront their own beliefs about authority, violence, and complicity. Far from being just a film about sadism and debauchery, it stands as an essential commentary on the dangers of authoritarianism and the fragility of human dignity. As Pasolini's audacious vision continues to provoke dialogue and inquiry, Salò has secured its place as a seminal work in the canon of transgressive cinema.

6. Oldboy (2003)

Director: Park Chan-wook

Oldboy is a masterful South Korean neo-noir thriller that follows the harrowing journey of Oh Dae-su, portrayed by Choi Min-sik, who is inexplicably imprisoned for 15 years in a mysterious room without any explanation. Upon his sudden release, Dae-su embarks on a relentless quest for revenge against his captor, only to uncover a shocking truth that forces him to confront his own past and choices. The film employs a genre-blending style, merging elements of action, drama, and psychological thriller, culminating in a narrative that is as beautifully crafted as it is brutal.

The film's depiction of vengeance is intricately layered, as Dae-su's quest unfolds through a series of shocking discoveries that reveal not only the depths of his own rage but the twisted machinations of his antagonist. A few standout moments include the infamous hall fight scene, choreographed with balletic precision, where Dae-su takes on numerous foes armed with nothing but a hammer. This scene beautifully symbolizes his transformation from victim to aggressor, emphasizing the raw determination that has built up during his years of captivity.

Park Chan-wook's direction is visually striking, characterized by dynamic camera angles and meticulous framing. The iconic "corridor fight" scene showcases a combination of long takes and impressive cinematography that immerses viewers in the visceral struggle. The use of color and lighting throughout the film is also significant—blending dark, moody tones with moments of vibrant hues to reflect emotional changes and emphasize particular story beats. For example, the somber warehouse used for Dae-su’s prison and the contrasting brightness during moments of revelation amplify the emotional weight of the narrative.

A recurring theme in Oldboy is the impact of isolation on identity. Dae-su’s imprisonment leads to a profound metamorphosis, as his sense of self deteriorates during his confinement. His experiences highlight the fragility of identity when one is stripped of autonomy and connection. As he navigates the external world after years of solitude, Dae-su struggles to reconcile with who he has become—an embodiment of both vengeance and despair.

The film also offers keen observations on societal issues, particularly around the themes of revenge and the consequences of one's actions. Dae-su’s journey serves as a critique of the cyclical nature of violence and the idea that revenge will lead to personal satisfaction. As he closes in on his captor, the narrative raises critical questions about justice, morality, and the human psyche, ultimately implying that vengeance only begets more suffering.

One of the most compelling aspects of Oldboy is its intricate plot twists, especially the shocking moment of revelation that recontextualizes the entire narrative. The encounter between Dae-su and his captor reveals a twisted bond forged through manipulation—highlighting the extremes of psychological torment. This pivotal moment not only serves as a turning point in the story but also compels viewers to reflect on the nature of revenge and its ability to cloud judgment.

Upon its release, Oldboy became a cornerstone of the "Vengeance Trilogy" and propelled South Korean cinema into the global spotlight. Its unique storytelling and shocking twists have influenced numerous films and directors worldwide. The film’s critical acclaim was further solidified when it won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival in 2004. Its intense style and profound narrative have inspired debates about morality in cinema, making it a key text in discussions of genre and narrative structure.

Oldboy is not just a thriller; it is a complex exploration of revenge, identity, and the psychological scars of trauma. Through its captivating storytelling and rich thematic depth, the film invites viewers to ponder the moral implications of vengeance and the human condition. Park Chan-wook’s audacious vision and Choi Min-sik's remarkable performance combine to create a cinematic experience that is both thrilling and thought-provoking. As Oldboy continues to resonate with audiences, it remains a quintessential example of the power of cinema to provoke thought and challenge perceptions of justice and retribution.

7. Seven (1995)

Director: David Fincher

Seven is a gripping psychological thriller that follows two detectives, David Mills (Brad Pitt) and William Somerset (Morgan Freeman), as they hunt down a serial killer who commits his murders based on the seven deadly sins: gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, lust, and pride. Set against a grim, rain-drenched urban backdrop, the film delves deep into the darkest aspects of human nature, illustrating the profound struggle between good and evil as the detectives race against time to save the killer's final victims.

The film’s exploration of morality and human depravity is both chilling and thought-provoking. Each murder, meticulously crafted to reflect one of the deadly sins, serves not merely as a plot device but as a deconstruction of societal flaws and human vulnerability. For instance, the grotesque "gluttony" scene establishes the killer's philosophical motivation, revealing a twisted belief that he is enacting divine judgment on those he deems morally corrupt. This profound moral questioning mirrors the detectives' internal struggles, particularly Somerset's philosophical cynicism contrasted with Mills's passionate idealism.

David Fincher's direction is characterized by its meticulous attention to detail and dark visual style. The film employs shadowy lighting and claustrophobic framing, evoking a sense of entrapment and despair that enhances the uneasy atmosphere. Notable is the use of color, particularly the perpetual greys and muted tones that saturate the film, reinforcing themes of hopelessness and decay. The opening credit sequence features disorienting close-up shots and heart-pounding music, immersing viewers directly into the film's disturbing psychological landscape.

The dynamic between Somerset and Mills is central to the narrative, encapsulating the film’s thematic depth. Somerset represents the weary, experienced detective who has seen the worst of humanity, often sharing philosophical musings on the human condition, which adds layers to the narrative. In contrast, Mills's youthful naivety and passion for justice create tension as he grapples with the gruesome reality of the case. Their relationship reflects a duality of belief systems—Somerset's growing cynicism versus Mills's unwavering commitment—culminating in a tragic but insightful climax.

Seven ventures into the human psyche with its bleak portrayal of urban life, challenging viewers to confront the despair that often accompanies societal decay. The film raises critical questions about justice, morality, and the relentless pursuit of meaning in a world filled with corruption. Somerset's reflections reveal his struggle between the lure of despair and the hope for redemption, making his character a poignant representation of the moral conflict present in the narrative.

The film’s climax is both shocking and thought-provoking, introducing an unexpected and horrifying twist that forces viewers to confront the consequences of revenge and melancholic acceptance. In the final moments, as Mills learns the deep and tragic truth behind the killer’s motivations, the film masterfully illustrates the notion that seeking justice can lead to devastating outcomes. The chilling line, "What’s in the box?" serves not only as a shocking plot reveal but also as a metaphor for the darkness that awaits when one's thirst for vengeance collides with reality.

Seven was groundbreaking for its dark themes and graphic content, paving the way for future psychological thrillers and influencing a generation of filmmakers. Its exploration of moral ambiguity resonated deeply with audiences, prompting discussions about the nature of evil and the ethical boundaries of justice. The film has been analyzed in various academic circles for its rich thematic elements and has maintained a lasting impact on the genre, solidifying Fincher's reputation as a master of suspense.

Seven is more than just a compelling murder mystery; it is a profound examination of human morality, the consequences of sin, and the psychological struggles inherent in the quest for justice. With its unforgettable performances, haunting visuals, and thought-provoking themes, the film remains a timeless classic that challenges viewers to confront the darker sides of human nature. David Fincher's work continues to resonate, making Seven an essential study in the realm of psychological thrillers that transcends its genre and provokes introspection long after the credits roll.

8. Visitor Q (2001)

Director: Takashi Miike

Visitor Q is a transgressive film that delves into the macabre dynamics of a dysfunctional family. The story revolves around a journalist named Q who arrives at the home of a disjointed family: a mother (played by Kiwako Harumoto) who has succumbed to addiction, a father who is a reclusive and abusive figure, and a son who is bullied at school. As the mysterious Visitor Q injects himself into their troubled lives, he exposes and amplifies their chaotic dysfunctions, leading to grotesque and often shocking interactions that draw the characters deeper into depravity.

The film challenges conventional narratives about family and societal norms, presenting a disturbingly satirical exploration of human depravity. Miike employs dark humor coupled with existential observations to challenge viewers' perceptions of traditional family values. For instance, In one moment, the characters engage in shocking acts of violence and sexual dysfunction, forcing audiences to confront both the absurdity and tragedy of their lives. The Visitor Q himself emerges as both a catalyst for change and a symbol of the darkest aspects of human nature, compelling viewers to question the boundaries of morality within familial relationships.

Miike's direction is characterized by its raw, unfiltered approach, embracing a documentary-esque style that enhances the film's visceral impact. The handheld camera work, combined with stark lighting and gritty visuals, creates an unsettling atmosphere that immerses viewers in the varying degrees of chaos surrounding the family. This gritty visual style contrasts with the film’s absurd situations, heightening the comedic yet horrifying absurdity of their existence.

Central to Visitor Q is the exploration of alienation and the search for identity within a decaying social framework. The film’s characters grapple with deep personal trauma, illustrating how familial ties can sometimes become chains of dysfunction rather than sources of support. The mother's addiction, the father's sadism, and the son’s bullying converge to form a toxic environment where individual identities are lost in the mire of collective misery. Through the introduction of Visitor Q, the film questions the nature of healing and transformation in such toxic environments, as he incites a mix of chaos and catharsis.

Miike's provocative portrayal of a perverse family dynamic serves as a critique of contemporary Japanese society, highlighting issues such as isolation and societal breakdown. The film's nonconformist stance reflects a wider commentary on the darker side of urban life in Japan at the time, delving into the ways that modernity and consumerism warp human relationships. The shocking elements in the film—cannibalism, necrophilia, and violence—serve to unsettle the audience while simultaneously reflecting deeper societal anxieties about identity, family dynamics, and societal decay.

Visitor Q is unflinching in its approach to taboo subjects, exploring themes of sexual abuse, consent, and the extremes of familial loyalty. One memorable scene features the family engaging in shockingly violent acts, which effectively serves to examine the limits of human behavior when pushed to the extremes. Miike's audacity in depicting such disturbing elements forces viewers to confront their discomfort and reflect on the motivations behind these actions, ultimately leading to compelling discussions about morality and social limits.

Visitor Q challenges viewers to face the unvarnished reality of a fractured family and the societal forces that shape them. Takashi Miike’s fearless direction and bold narrative choices create a grim yet thought-provoking experience that remains relevant and provocative for contemporary audiences. It serves as both a disturbing examination of human depravity and a scathing critique of societal norms, ensuring that it will linger in the minds of those willing to confront its unsettling truths. Despite—or perhaps because of—its transgressive content, Visitor Q holds a mirror to the depths of human experience, pushing viewers toward a greater understanding of the complexities of familial and social relationships.

9. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)

Director: John McNaughton

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is a harrowing exploration of the life of Henry Lee Lucas, portrayed by Michael Rooker, whose chilling portrayal of a sociopathic murderer paints a disturbing yet realistic picture of violence and alienation. The film follows Henry, a drifter who, alongside his friend Otis (Tom Towles), descends into a life of brutal murder, dipping into the darkness of the human psyche without glorifying it or presenting it as sensational entertainment. Best known for its raw intensity and documentary-style realism, the film eschews traditional narrative structures, opting instead for an unflinching, almost voyeuristic portrayal of its subject matter.

What sets Henry apart from other true-crime films is its commitment to portraying the banalities of evil. Rather than focusing solely on crime scenes or the excitement of the hunt, the film provides an unsettling glimpse into the mundane life of a serial killer. For instance, one of the film's pivotal scenes takes place in a cramped apartment where Henry and Otis engage in trivial conversation after committing heinous acts. This juxtaposition forces viewers to confront the unsettling nature of evil within the context of everyday life, breaking the myth of the serial killer as a larger-than-life monster.

The film's stark cinematography heightens the impact of its disturbing content. Shot with a gritty, low-budget aesthetic, McNaughton employs a mix of handheld camera work and static shots that lend the film a documentary-like realism. The use of natural light and muted colors not only underscores the bleakness of Henry's existence but also places viewers uncomfortably close to the violence and depravity being depicted. The unadorned visual style enhances the tension and makes the horror feel immediate and unavoidable.

Michael Rooker's performance as Henry is a masterclass in understated horror. He brings a chilling calmness to the character, emphasizing Henry's sociopathic detachment rather than caricaturing him as a stereotypical villain. The film delves into Henry's psyche, illuminating his complex relationship with Otis and his eerie interactions with women, which serve to humanize him while simultaneously enhancing his monstrous likeness. For instance, his chillingly casual demeanor during a murder is juxtaposed with moments of unexpected vulnerability, presenting a multifaceted portrayal of a deeply troubled individual.

A dominant theme in Henry is the alienation of individuals within society, particularly as it pertains to Henry and Otis's detachment from human emotions and societal norms. The film’s exploration of their relationship touches on male camaraderie but also highlights a deep-seated emotional void, suggesting that societal neglect can manifest in horrific ways. Henry's ability to brutally murder while maintaining human interactions that seem ordinary underscores the desensitizing effects of violence in culture, urging viewers to reflect on how proximity to violence can distort perceptions of empathy and morality.

Released in the mid-1980s, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer shocked audiences with its raw depiction of violence, leading to significant controversy and debate about the nature of violence in film. The film attained notoriety for its graphic content, and it was subject to censorship in various regions upon its release. Over time, however, it has been recognized as a seminal work in the horror genre, lauded for its unflinching approach and impact on the portrayal of serial killers in cinema. It influenced subsequent films that aimed to tackle the subject matter with similar levels of seriousness and realism, including Monster and The Silence of the Lambs.

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is not merely an exploration of evil—it is a meditation on the nature of violence, alienation, and the unsettling reality that monsters can exist within mundane society. Its gritty realism, engaging character work, and authentic portrayal of human depravity challenge audiences to confront their own moral boundaries. As the film delves into the psyche of a serial killer without romanticizing his actions, it serves as a critical examination of society’s fascination with violence and the consequences of indifference. Ultimately, Henry forces viewers to reflect on the darkness that lurks within humanity and the thin line between observer and complicit witness.

10. The Chaser (2008)

Director: Na Hong-jin

The Chaser is a gripping South Korean thriller that follows an ex-detective turned pimp, Joong-ho (Kim Yoon-seok), who is on a frantic hunt for one of his missing prostitutes after she fails to return from an appointment. As he investigates, Joong-ho discovers that a serial killer, known as the "uniquely sadistic" murderer, has been targeting sex workers in the area. The film unfolds in real-time, creating a relentless atmosphere of tension as Joong-ho races against time to uncover the truth and save his missing employee.

The film's narrative is taut and engaging, expertly balancing elements of suspense, emotional depth, and social commentary. Joong-ho’s descent into desperation highlights the darker aspects of society, revealing the vulnerability of those on the margins—particularly sex workers who are often dismissed by law enforcement and society. The chilling portrayal of the killer’s methodical approach to murder offers a stark juxtaposition to Joong-ho's frantic and emotionally charged quest, making the narrative particularly impactful.

Na Hong-jin employs a gritty visual style that accentuates the film's unflinching realism. The use of handheld cameras and tight framing places viewers uncomfortably close to the action and heightens the sense of urgency. The dark, rain-soaked streets of Seoul serve as a fitting backdrop for the film, reflecting the grim realities of the characters’ lives. Flashes of stark, brutal imagery throughout the film—particularly during the killer’s acts of violence—create a haunting experience that lingers long after viewing.

Kim Yoon-seok delivers a compelling performance as Joong-ho, capturing the complexity of his character’s motivations. Initially portrayed as a flawed yet relatable protagonist striving for redemption, Joong-ho's desperation leads him down increasingly morally ambiguous paths. His interactions with the killer reveal the psychological toll of his pursuit—one moment, he is determined and resourceful; the next, he is overwhelmed by guilt and a sense of impending failure. The film reflects on the duality of his character, forcing viewers to grapple with their perceptions of heroism and villainy.

The Chaser presents a critical examination of societal failures, particularly concerning law enforcement's treatment of vulnerable populations. The film starkly illustrates the inadequacies of the police as Joong-ho initially finds himself at odds with the system, leading to intense frustration as he realizes that finding the truth relies on his own tenacity rather than institutional support. This critique of authority serves as a compelling commentary on the moral complexities in the pursuit of justice, raising questions about what lengths one should go to in order to protect others.

Beyond its gripping suspense, the film touches upon significant socio-economic issues in South Korea, including the stigmas surrounding sex work. Joong-ho's history and that of his missing prostitute highlight the precarious conditions faced by those living on the fringes of society. The Chaser prompts a dialogue about systemic neglect and societal indifference toward marginalized individuals, illustrating how these dynamics can result in dire consequences.

The film's real-time structure amplifies the tension and urgency throughout the narrative. As Joong-ho races against the clock to find the killer and rescue the missing woman, the pacing enhances the brutal reality of the situation, keeping viewers on edge. This technique mirrors the relentless pursuit of time—reflecting themes of desperation and the sometimes futile quest for justice.

The Chaser is an exhilarating yet darkly poignant meditation on the nature of evil, the pursuit of justice, and the struggles of society's outcasts. Its engaging narrative, strong performances, and visceral direction combine to create a film that is both thrilling and thought-provoking. Na Hong-jin's adept storytelling compels the audience to face uncomfortable truths about moral ambiguity and societal failings, ensuring that The Chaser resonates as a powerful commentary on the human condition and the lengths we go to in our quest for justice and redemption.

11. Ichi (2003)

Director: Fumihiko Sori

Ichi is a reimagining of the iconic character from the classic Zatoichi film series, focusing on the story of a blind female assassin named Ichi (played by Haruka Ayase) who wanders through the countryside, seeking vengeance for the wrongs she has endured. Unlike her male counterpart, Ichi combines exceptional martial arts skills with a deeply emotional backstory, painting a portrait of a young woman shaped by trauma and resilience. As she encounters various yakuza members and criminals, her journey reveals themes of redemption, identity, and the complexities of violence.

The film deftly explores the intersection of trauma and violence through Ichi’s character. Raised in an abusive environment, her blindness serves as a metaphor for her emotional turmoil and social isolation. The transformation of Ichi into a lethal assassin is marked by both physical prowess and psychological scars, inviting audiences to empathize with her struggles. For example, her internal conflict is poignantly depicted in a scene where she hesitates before exacting her revenge, torn between her need for vengeance and the remnants of her humanity. This emotional depth differentiates Ichi from typical action films and complicates the narrative of retribution.

Visually, Ichi stands out with its striking cinematography and choreography. The use of vivid colors contrasts with the film's dark themes, with beautiful landscapes juxtaposed against scenes of brutal violence. The action sequences are expertly choreographed, blending traditional samurai style with modern cinematic techniques. A notable scene involves a stylized fight against multiple adversaries, utilizing slow-motion effects to amplify the tension and showcase Ichi’s skills while simultaneously highlighting the emotional weight of the confrontation.

Haruka Ayase’s portrayal of Ichi is both powerful and nuanced, capturing her transformation from a timid, vulnerable girl into a formidable assassin. Her performance conveys a complex mix of emotional vulnerability and fierce determination. The film also introduces a notable supporting character, a yakuza enforcer named Tadao (played by Shun Oguri), whose interactions with Ichi reveal deeper layers of moral complexity and offer moments of unexpected tenderness amidst the violence. Their evolving relationship adds emotional stakes to the narrative, showcasing how moments of connection can arise even in a world rife with brutality.

Ichi challenges traditional notions of heroism by exploring the cyclical nature of violence. The film does not romanticize Ichi’s lethal abilities; instead, it presents violence as a deeply painful reality intertwined with her quest for self-identity and justice. In one poignant moment, Ichi reflects on her actions, questioning whether vengeance truly brings solace or merely perpetuates a cycle of suffering. This thematic exploration encourages viewers to ponder the moral ramifications of their characters' choices, reinforcing the film's depth beyond its action-packed exterior.

By recontextualizing the blind assassin trope, Ichi engages with the cultural legacy of the samurai genre while adding a fresh perspective through the lens of gender. The film addresses societal perceptions of femininity and strength, showcasing how Ichi defies gender norms in her pursuit of vengeance. Additionally, the film draws from historical societal issues, including the marginalization of women in both traditional and contemporary settings, making it resonate with modern audiences.

Ichi is a visually stunning and emotionally charged exploration of vengeance, identity, and the haunting effects of trauma. Fumihiko Sori’s directorial prowess breathes new life into a classic character, crafting a narrative that stands apart from its predecessors. Through its blend of action and emotional complexity, Ichi invites viewers to reflect on the nature of violence and the quest for redemption, presenting a rich narrative tapestry that extends beyond mere spectacle. The film serves as a potent reminder that, even in the midst of darkness, the human spirit can seek healing and understanding, challenging the boundaries of revenge and moral choice.

12. Gozu (2003)

Director: Takashi Miike

Gozu is a surreal and nightmarish journey into the absurd, characteristic of Takashi Miike's signature style. The film follows a yakuza member, Minami (played by Tadanobu Asano), who is tasked with disposing of his mentally unstable boss, only to find himself engulfed in a bizarre series of events that transcend reality. As he navigates through a disorienting world filled with strange encounters and grotesque characters, Minami’s journey unfolds like a fever dream, challenging viewers’ perceptions of sanity, identity, and the absurdity of existence.

The film is replete with surreal imagery and bizarre scenarios that reflect the chaotic inner life of its protagonist. One memorable scene occurs when Minami encounters a woman housing a mysterious cow-like creature. This bizarre being serves as both a physical manifestation of his confusion and a critique on the nature of masculinity and power within the yakuza culture. The film's symbolism often alludes to broader themes of identity crisis and the struggle for autonomy in a world dominated by absurdity.

Miike's direction is marked by its inventive visual style and non-linear storytelling. The cinematography often blurs the line between dream and reality, employing strange angles and stark contrasts that evoke a sense of dislocation. The use of long takes and sudden cuts enhances the disorienting experience, compelling viewers to adapt to its unpredictable rhythm. The film frequently shifts between moments of dark comedy and sheer horror, creating an unsettling atmosphere that captivates and unsettles in equal measure.

Tadanobu Asano delivers a compelling performance as Minami, skillfully navigating the character’s descent into existential confusion. As Minami grapples with the loss of his boss, his journey becomes increasingly introspective. The film introduces a diverse cast of eccentric characters, including a transgender woman known as “the cow,” who plays a pivotal role in Minami’s transformation. Each character serves to push Minami further into the depths of his psyche, leading him to confront the absurdities of his life and the nature of his identity.

At its core, Gozu engages with themes of absurdity and the search for meaning in a chaotic world. The film’s surreal elements reflect the existential crisis faced by Minami, suggesting that traditional narratives and identities are often constructs that can unravel unexpectedly. The exploration of themes such as loyalty, disillusionment, and the fluidity of identity resonates throughout the film, encouraging viewers to contemplate their own perceptions of reality and the absurdities inherent in societal norms.

Miike’s film acts as a critique of yakuza culture and the rigid expectations placed on masculinity. The surreal approach highlights the absurdity of these expectations, while simultaneously exposing the emotional vacuum experienced by those who adhere to them. Minami’s journey reflects the struggle for personal freedom in a world that often prioritizes conformity and violence, making it a poignant commentary on the pressures imposed by society.

Aside from its surface-level absurdity, Gozu delves into the emotional depths of its characters. Minami’s relationship with his boss is layered with complexity, hinting at feelings of loyalty intertwined with fear and confusion. This exploration culminates in moments of profound vulnerability, as Minami navigates his feelings of alienation, questioning his own worth and identity throughout the chaotic events surrounding him.

Gozu is a fantastical exploration of the absurd, wrapped in the guise of a yakuza film. Takashi Miike's unfiltered vision confronts audiences with challenges to conventional narratives, resulting in a surreal experience that reflects deeper truths about existence, identity, and the chaos of modern life. By intertwining dark humor with the grotesque, Gozu transcends the typical gangster genre, serving as a compelling reflection on the nature of reality and self. It is a film that refuses to conform to viewer expectations, leaving a lasting impact through its audacious storytelling and complex thematic undertones.

13. Bronson (2008)

Director: Nicolas Winding Refn

Bronson is a visceral and stylized exploration of the life of Michael Peterson, who adopts the notorious alias Charles Bronson as he becomes one of Britain’s most infamous criminals. The film chronicles Bronson’s life from his troubled childhood to his transformation into a violent figure known for his flamboyant personality and brutal acts in prison. With an avant-garde approach, the film presents Bronson not merely as a criminal but as a complex individual wrestling with identity, fame, and the primal instinct for violence within the confines of a broken system.

The film is based on the real-life story of Charles Bronson, whose persistent incarceration and propensity for violence led him to become a media sensation. One poignant aspect of the narrative is Bronson's self-awareness and his frequent reflections on the nature of fame and the persona he crafted. Refn uses surreal sequences interspersed with stark realism to depict Bronson's internal battles. In one memorable scene, Bronson appears in a theatrical performance, directly addressing the audience, which emphasizes his desire for recognition and control over his own narrative, blurring the line between performer and subject.

Visually, Bronson is striking, utilizing a mix of bold colors and stark contrasts to create an unsettling atmosphere. The film features cinematic techniques that enhance its psychological depth, including rapid cuts, varying film speeds, and unsettling close-ups. Refn’s choice of framing often evokes a sense of claustrophobia, reflecting Bronson's confinement and the cyclical nature of violence in his life. The unique blend of stylized elements with raw brutality heightens the film's emotional impact, making the audience both captivated and disturbed.

Tom Hardy's portrayal of Charles Bronson is nothing short of extraordinary; he embodies the character with a visceral intensity that brings both charisma and menace to the role. Hardy’s physical transformation for the part—adding significant muscle mass and adopting Bronson’s distinctive mannerisms—allows for a nuanced performance that captures the complexities of his character. The film’s exploration of Bronson as an artist, particularly through his love of painting and self-expression, adds layers to his character, illustrating his search for identity beyond the violence that defines him.

Bronson delves into the themes of violence as both a form of expression and a means of establishing identity. The narrative explores how Bronson uses brutality as a statement against the institutional forces that seek to confine him. His violent acts, depicted with an almost theatrical flair, serve as a critique of societal norms and the way they shape individual identity. Refn draws parallels between Bronson’s life and the art of performance, suggesting that violence can be seen as a grotesque art form when stripped of context and presented for public consumption.

The film offers a critique of the prison system and societal views on criminality and punishment. While Bronson’s notoriety grows, it raises questions about the spectacle of violence in media and society’s fascination with criminals. In one compelling scene, Bronson’s infamy is celebrated in tabloid headlines, reflecting how society often glorifies violence while simultaneously condemning it. This duality serves as an indictment of a culture that both sensationalizes and marginalizes individuals like Bronson, challenging viewers to scrutinize their own responses to crime and violence.

Throughout Bronson, the audience is invited to witness the psychological toll that years of confinement take on its subject. Beyond his infamous acts of violence, moments of vulnerability are revealed, prompting reflection on the nature of punishment and its effect on identity. Bronson’s insatiable need for notoriety juxtaposed with his moments of introspection captures the complexity of a man who yearns for connection yet finds himself trapped in a cycle of violence and isolation.

Bronson is a bold, provocative exploration of the nature of violence, identity, and fame, propelled by Tom Hardy's magnetic performance and Nicolas Winding Refn's audacious direction. Through its stylized portrayal of a life marked by chaos and confinement, the film pushes boundaries while inviting deep reflections on societal constructs related to crime and punishment. Bronson transcends the typical biographical crime film, creating a thought-provoking experience that challenges audiences to confront their perceptions of morality, identity, and the profound impacts of violence on the human psyche. Ultimately, it portrays Charles Bronson not merely as a criminal but as a complex figure wrestling with the forces that shape his existence, leaving a lasting impression on viewers long after the credits roll.

14. No Country for Old Men (2007)

Directors: Joel and Ethan Coen

Adapted from Cormac McCarthy's acclaimed novel, No Country for Old Men is a haunting exploration of morality and fate set against the arid backdrop of West Texas. The film follows three main characters: Llewellyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a welder who stumbles upon a drug deal gone wrong and takes a briefcase full of cash; Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a relentless hitman with a chilling belief in fate and chance; and Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), an aging lawman grappling with the violence and chaos that has overtaken his once-familiar landscape. The film weaves themes of fate, choice, and the changing nature of evil into a narrative that builds tension and psychological depth.

The Coen Brothers masterfully present the philosophical underpinnings of violence and morality through the characters’ arcs. Moss’s decision to take the money sets off a chain reaction of violence that serves as a catalyst for the film’s exploration of personal responsibility and moral ambiguity. As he attempts to evade Chigurh, it becomes clear that despite his resourcefulness, Moss is ultimately outmatched by the inevitability of violence and fate. The stark contrast between him and Chigurh highlights the existential theme throughout the film—the idea that some forces in life are beyond human control.

Cinematographer Roger Deakins crafts a visually stunning landscape that reflects the film's themes. The sweeping vistas of the Texas plains serve as both a beautiful backdrop and a character in their own right, emphasizing the vast, often unforgiving nature of the environment. The minimalist style, marked by long takes and sparse dialogue, creates an atmosphere of tension and foreboding. Notably, the absence of a traditional musical score enhances the film’s realism and suspense, allowing the haunting sound of silence to amplify moments of dread.

Javier Bardem’s portrayal of Anton Chigurh is chilling and unforgettable, cementing his status as one of cinema’s most iconic villains. Chigurh operates under a strict personal code, believing in a twisted sense of morality guided by fate. His use of a coin toss to determine the fate of his victims further exemplifies his cold pragmatism and the randomness of life and death. In one chilling sequence, he confronts a gas station owner, engaging in a philosophical discussion that illustrates his worldview and highlights the arbitrary nature of violence. This emotional detachment allows the audience to see him not just as a villain, but as a manifestation of the chaos and brutality present in the world.

Sheriff Bell’s character represents the frailty of traditional values in the face of overwhelming violence and moral decay. His introspective dialogue and reflective nature serve as a counterpoint to the brutal action occurring around him. Bell’s conversations often reveal a profound sense of despair, as he grapples with the reality that he can no longer protect his community or understand the new forms of violence that plague it. His final monologue, in which he recounts a dream about his father, encapsulates his longing for a simpler time and a righteous world that seems increasingly out of reach.

The film addresses broader societal concerns, particularly the changes in American culture and morality. As Bell struggles to comprehend the violence that surrounds him, he represents a fading generation of lawmen who believe in justice and order. Chigurh, in contrast, symbolizes an emerging nihilism that rejects traditional morality—a reflection of contemporary existential crises. This notion resonates with audiences as it positions No Country for Old Men as a commentary on the disillusionment of modern society and the challenges of maintaining moral clarity in an increasingly chaotic world.

The film's pacing and tension build to a climax marked by a sense of dread and inevitability. The final confrontation is not glorified; rather, it reflects the harsh reality of life choices and their consequences. The lack of a conventional resolution leaves viewers contemplating the implications of fate versus free will, which is embodied in the film’s unresolved mysteries. This open-endedness heightens the emotional impact of the narrative, encouraging discussions about the nature of morality in a world rife with ambiguity.

No Country for Old Men is a masterful film that transcends typical genre boundaries to deliver a profound exploration of fate, morality, and the nature of evil. The Coen Brothers’ adept storytelling, combined with stellar performances and striking cinematography, create a hauntingly unforgettable cinematic experience. With its rich thematic depth and philosophical inquiries, the film compels viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about life, violence, and the ever-evolving landscape of morality. As Sheriff Bell reflects on the darkness he faces, audiences are left pondering their own beliefs about justice and the inevitable passage of time, solidifying No Country for Old Men as a modern classic that resonates deeply in its examination of human experience.

15. Benny's Video (1992)

Director: Michael Haneke

Benny's Video is a chilling exploration of alienation and the desensitization to violence in a media-saturated society. The film centers on a teenager named Benny (Arno Frisch), who becomes increasingly withdrawn and obsessed with video technology. After witnessing a brutal murder in a video, he becomes enraptured by the violent imagery, leading him to commit a shocking act of violence himself. The film examines the consequences of an obsession with media and the blurred lines between reality and simulation, culminating in a disturbing reflection on the effects of isolation and the appetite for violence.

The film's premise highlights the disconnect between reality and the spectacle of violence as mediated through technology. Benny's initial fascination with a home video of a pig slaughter serves as an unsettling foreshadowing of his eventual actions. This scene exemplifies the disturbing desensitization to brutality that can occur when violence is viewed as mere entertainment. Haneke deftly critiques how media consumption shapes perceptions of reality, compelling audiences to question the extent to which they engage with violent imagery in their own lives.

Haneke employs a stark and controlled visual style that enhances the film's unsettling atmosphere. The use of long takes and static shots allows moments of tension to linger, drawing viewers into Benny's increasingly troubled psyche. The camera often observes rather than intervenes, creating a sense of voyeurism that mirrors Benny's own detached engagement with the world around him. This technique serves to build tension and discomfort, compelling audiences to grapple with their own reactions to the unfolding horror.

Arno Frisch's performance as Benny is both chilling and deeply unsettling. The character's transformation from an ordinary teenager to a cold, calculating individual underscores the film's exploration of the impact of media on youth. Benny's interactions with his parents and friends reveal a profound disconnect and emotional detachment, illustrating how his obsession with video has eroded his sense of empathy. For example, his coldly pragmatic approach to the aftermath of his violent act underscores his increasing alienation from moral responsibility.

Benny's Video delves into the theme of psychological isolation in an increasingly mediated society. Benny’s withdrawal into his own world reflects a broader commentary on the disconnection many feel in the face of modern technology. Haneke challenges viewers to confront the consequences of this alienation: how the desire for escapism through media can lead to a disturbing disconnection from reality and moral accountability. The portrayal of Benny's family dynamic shows further complexities, with parents who are largely absent from their son’s emotional life, highlighting the failures of familial communication and support.

The film serves as a critique of how society interacts with violence in media, provoking discussions about the normalization of brutality in popular culture. The chilling nature of Benny’s actions begs the question: how culpable are we when we consume media that trivializes violence? Benny’s final act of violence is not portrayed as sensational but rather as a natural progression of his desensitized worldview, inviting viewers to reflect on their own relationships with media and its moral implications.

The tension builds throughout the film as Benny grapples with the consequences of his actions. The climax, which culminates in a shocking act that mirrors the violence he had previously consumed on video, serves as a powerful commentary on the dangers of desensitization. The scene is portrayed with a stark realism that leaves a lasting impact, forcing audiences to confront the unsettling reality of Benny's transformation and the broader societal implications of such behavior.

Benny's Video is a provocative and unsettling exploration of isolation, violence, and the impact of media on human behavior. Michael Haneke's unflinching direction and Arno Frisch's haunting performance create a film that resonates with contemporary concerns about the desensitization that accompanies modern technology. By presenting a chilling narrative that blurs the lines between reality and simulation, Haneke invites viewers to scrutinize their own perceptions and engagement with violent imagery and the moral responsibilities that accompany it. Ultimately, Benny's Video stands as a significant and thought-provoking commentary on the complexities of youth, media influence, and the seductive quality of violence in contemporary culture.

16. Audition (1999)

Director: Takashi Miike

Audition is a groundbreaking psychological horror film that masterfully combines elements of romance and suspense. The story follows Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi), a middle-aged widower who is urged by his friends to find a new partner. To facilitate this, he devises a scheme to hold a fake audition for a film, hoping to find the perfect woman. Among the contestants is Asami (Eihi Shiina), a seemingly demure and charming young woman with a dark and hidden past. As Aoyama becomes infatuated with Asami, the narrative gradually shifts from a romantic setup to a harrowing exploration of desire, manipulation, and psychological trauma.

The film intricately explores the themes of deception and the facades people construct in relationships. As Aoyama becomes increasingly enamored with Asami, viewers witness the gradual unraveling of his character's understanding of intimacy and trust. The audition process itself becomes a powerful metaphor for the performance of self in dating and relationships, showcasing how both Aoyama and Asami hide their true selves under layers of charm and allure. Asami’s character becomes a haunting representation of the dangers of idealizing love and the hidden depths that can lie beneath a surface of apparent vulnerability.

Miike employs a deliberate visual style that contrasts serene, romantic imagery with the unsettling transformation of the narrative. The lush cinematography during the film's early romantic sequences draws the audience into Aoyama's idealized world, making the subsequent shift into horror even more shocking. The use of lighting and color plays a critical role; warm, inviting tones dominate the early scenes, while the tonal shift to cold, stark lighting emphasizes the psychological horror building beneath the surface. This stylistic contrast enhances the film’s emotional impact and amplifies the sense of dread.

Eihi Shiina’s portrayal of Asami is both captivating and chilling, as her character transitions from an alluring, innocent exterior to a terrifying embodiment of vengeance and madness. This duality is illustrated in a pivotal scene where Asami confronts Aoyama about his true intentions, revealing her complex psyche. Her unsettling calmness during graphic moments serves as a profound commentary on the nature of trauma and the psychological scars that can manifest in unexpected and horrific ways. The contrast between Aoyama's perceived normality and Asami's unsettling reality creates a layered portrayal of love turned toxic, enriching the narrative's depth.

The dynamics of power and control are central to Audition. As the film progresses, it subverts traditional gender roles and expectations in relationships. Aoyama initially appears to be the one in control, orchestrating the audition process as a means to fulfill his desires. However, as Asami reveals her darker tendencies, the power shifts, and the film delves into themes of dominance and submission. The shocking climax of the film, which features graphic violence and psychological manipulation, forces viewers to confront their own interpretations of control in intimate relationships and the potential for darkness within desire.

Released during a period of increased visibility for women's issues in Japan, Audition can be interpreted as a commentary on the societal expectations placed on women, particularly in romantic and domestic contexts. Asami's backstory—a victim of sexual exploitation—serves to highlight the darker aspects of gender dynamics. The film forces viewers to confront uncomfortable realities about how women can be perceived and commodified in a patriarchal society. This critique is woven thoughtfully into the horror narrative, encouraging deeper engagement with the film's themes beyond mere shock value.

The film's pacing, particularly in the first two acts, allows for a slow build-up of tension and character development that immerses audiences in Aoyama's world before plunging them into chaos. The psychological horror unfolds gradually, creating an oppressive atmosphere that elicits a wide spectrum of emotions—from empathy for Aoyama's plight to horror at Asami's true nature. The final scenes, particularly the haunting imagery presented alongside Aoyama’s fate, compel viewers to grapple with their own feelings of discomfort, fear, and even disbelief at the extremes of human behavior and the psyche.

Audition stands as a seminal work in the horror genre and a profound exploration of psychological torment, desire, and the complexities of human relationships. Takashi Miike's direction, coupled with outstanding performances and haunting cinematography, crafts a film that transcends its genre to become an unsettling meditation on love and the dark motivations that can lie beneath. Through its intricate narrative and complex character dynamics, Audition challenges audiences to reflect on their perceptions of romance, trust, and the boundaries of human desire, leaving a lasting impression that continues to resonate deeply in contemporary discussions of gender and identity.

17. Scum (1979)

Director: Alan Clarke

Scum is a gritty and unflinching British drama that offers a harrowing glimpse into life inside a young offenders' institution. The film takes a stark and harsh look at the experiences of its main character, Carlin (Ray Winstone), as he arrives at a correctional facility infamous for its brutal environment. As Carlin navigates the brutal hierarchy among inmates, the film exposes themes of violence, power dynamics, and the dehumanization rampant within the penal system.

The film's raw portrayal of institutional brutality presents a compelling critique of the prison system and its impact on young offenders. The character of Carlin represents the struggle for survival and autonomy in a system designed to strip individuals of their dignity. For instance, his confrontation with the established order among inmates highlights the oppressive nature of the institution, where power is maintained through violence and intimidation. This dynamic illustrates how incarceration can perpetuate cycles of abuse and aggression, ultimately failing its intended purpose of rehabilitation.

Clarke's directorial style is characterized by a documentary-like realism, employing handheld cameras and natural lighting to immerse viewers in the oppressive atmosphere of the prison. The film's visual aesthetics contribute to its unsettling tone, capturing the cold, bleak environment in which the characters exist. The use of long takes and minimal cuts allows the audience to experience the suffocating intensity of Carlin's world, making even mundane interactions feel charged with tension.

Ray Winstone’s portrayal of Carlin is powerful and emotionally resonant. The character's journey from a vulnerable newcomer to a dominant figure within the prison hierarchy illustrates the transformative—and often corrupting—effects of violence inherent in such institutions. One especially poignant scene captures Carlin’s internal conflict as he grapples with his morality and the harsh realities he faces, demonstrating the psychological toll of survival in an environment where empathy is a liability.

At its core, Scum addresses the pervasive themes of violence and the quest for power. The film doesn’t shy away from depicting graphic acts of brutality among inmates and the guards, emphasizing the desensitization to violence that occurs in such environments. Carlin’s attempts to find a sense of agency culminate in a chilling assertion of power, ultimately leading to a tragic conclusion that prompts viewers to reflect on the harsh realities of institutional life and the cyclical nature of violence. The film suggests that the institution, rather than rehabilitating young offenders, often reinforces their aggressions and traumas.

Released in a period marked by social unrest and political change in the UK, Scum serves as a powerful commentary on the failures of the juvenile justice system. The film critiques the systemic neglect and brutality faced by marginalized youth, raising questions about social justice and the treatment of individuals within the correctional system. The shocking depiction of daily life in the institution serves to illuminate the broader societal issues surrounding crime, punishment, and the inherent struggle for dignity in the face of oppression.

Initially banned by the British Board of Film Censors for its graphic content and harsh portrayal of institutional life, Scum has since garnered critical acclaim and is considered a seminal work in British cinema. Its unflinching approach to social commentary has influenced countless filmmakers and provided a stark blueprint for future depictions of prison life in film. The raw potency of Winstone's performance alongside Clarke's direction elevates Scum to a significant cultural artifact that continues to provoke discussions about crime, punishment, and societal responsibility.

Scum remains a harrowing exploration of life within a young offenders' institution, delivering a potent critique of the penal system and its inherent failures. Alan Clarke's powerful direction, coupled with Ray Winstone’s gripping performance, creates a film that is both unsettling and thought-provoking. By focusing on themes of violence, power, and the struggle for identity, Scum invites viewers to confront difficult truths about society’s treatment of its most vulnerable and the cyclical nature of abuse within institutional settings. The film's lasting impact makes it an essential commentary on the human condition and a profound exploration of the consequences of systemic neglect and aggression.

18. City of God (2002)

Directors: Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund

City of God is a powerful and visually stunning Brazilian crime drama that chronicles the rise of organized crime in the Cidade de Deus (City of God) neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro from the 1960s to the 1980s. The film follows the lives of several characters, particularly a young aspiring photographer named Buscapé (Alexandre Rodrigues), as they navigate the complexities of life in a volatile and impoverished community. Through its rich tapestry of interconnected stories, the film provides a raw and unflinching look at the effects of poverty, gang violence, and systemic inequality.

The film’s narrative unfolds through Buscapé's eyes, giving the audience a personal and intimate perspective on the realities faced by the residents of the City of God. One of the key themes is the loss of innocence amid a backdrop of violence and crime. As Buscapé witnesses the brutal rise of gang leaders such as Li’l Zé (Leandro Firmino) and the disintegration of community trust, viewers are compelled to confront the harsh realities of life in the favelas. The film doesn't depict crime in a sensationalized manner but instead focuses on the socioeconomic factors that contribute to the cycle of violence, allowing audiences to empathize with characters who are often caught in a web of desperation.

The film is notable for its dynamic cinematography, which combines frenetic camera movements, vibrant colors, and a mix of documentary-style realism and stylized editing. The use of hand-held cameras creates an immersive experience that draws viewers into the chaotic environment of the favela. The cross-cutting between different timelines and characters adds to the film's intensity and effectively conveys the interconnectedness of their lives. For example, thrilling action sequences are interspersed with moments of reflection, enhancing the emotional weight of the narrative and emphasizing the harsh realities of survival in the City of God.

The diverse array of characters in City of God exemplifies the complexity of life within the favela. Each character—whether they be aspiring musicians, small-time criminals, or innocent bystanders—represents different facets of the community’s resilience and vulnerability. Li’l Zé’s fierce ambition to rise to power highlights the seductive nature of violent crime, while characters like Buscapé serve as embodiments of hope and ambition in the face of stark adversity. One particularly striking narrative thread follows a group of young boys who, in an effort to escape their circumstances, take up photography, showcasing the stark contrast between their aspirations and the lurking violence around them.

City of God serves as a poignant critique of social and economic inequalities that plague Brazilian society. The film presents a society where systemic poverty robs individuals of opportunities, forcing them to resort to crime as a means of survival. The character arcs often illustrate the limited options available to those born into the favela, highlighting how cycles of violence and crime become normalized. Scenes depicting the stark contrast between the rich neighborhoods surrounding the favelas and the devastated conditions within the City of God emphasize the harsh divide in socioeconomic status and access to resources.

Set against the backdrop of a rapidly changing Brazil, the film provides insight into the historical and cultural evolution of Rio de Janeiro during the latter half of the 20th century. The emergence of drug trafficking and gang violence in the country is documented with vivid realism, highlighting the intersection between crime and societal change. Additionally, City of God touches upon themes of community, identity, and resilience, capturing the essence of Brazilian culture and the struggles that shape it.