8 Best Movies Like Taste of Cherry | Similar-List

Table Of Contents:

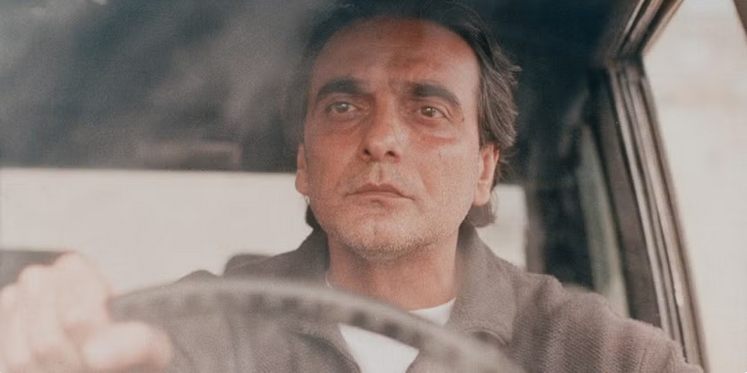

Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry is a haunting meditation on existence, offering a subtle yet profound exploration of life, death, and the pursuit of meaning. The film follows Mr. Badii, a man in search of someone who can help him end his life. As he drives through the Iranian countryside, his encounters with strangers—each with their perspectives on life—force him to confront not only his imminent death but also the emotional complexities of living. The film’s minimalistic storytelling and slow, deliberate pacing invite viewers to reflect deeply on their existence and the choices that define their lives.

At its heart, Taste of Cherry is a meditation on mortality. The film poignantly examines the space between life and death, particularly how contemplating one’s end can lead to reevaluating what has come before. As Mr. Badii speaks with strangers, from soldiers to taxidermists, each conversation subtly reveals his internal conflict and the universal search for meaning. The film’s sparse dialogue and contemplative cinematography emphasize the fragility of life and the complex emotions tied to ending one’s existence, challenging viewers to question what gives life meaning and whether peace can ever truly be attained.

The film's structure is built around a series of encounters unfolding within a confined time frame. These interactions—whether with a potential helper or an accidental passerby—serve as quiet moments of reflection that propel the narrative toward a contemplative conclusion. Kiarostami’s use of silence, long takes, and the absence of dramatic flourishes emphasizes the stillness of life, offering a profound contrast to the typical rush of daily existence. Focusing on subtle exchanges and the emotional tension of what is left unsaid, the film creates a space for viewers to explore their relationship with mortality.

Taste of Cherry is not alone in exploring existential questions and the quest for meaning in the face of death. Many films share similar thematic concerns, ranging from quiet, meditative reflections on life’s impermanence to more surreal or whimsical treatments of mortality. While offering different tones and narrative styles, these films all delve into deep questions about human existence, each exploring death, grief, and the fragility of life in its own unique way. Whether through humor, sadness, or introspection, they offer profound reflections on the human condition, inviting viewers to contemplate the meaning of their own lives.

8 Best Movies Like Taste of Cherry

Death at a Funeral (2007)

At first glance, Death at a Funeral might seem like an unlikely recommendation for fans of Taste of Cherry. Still, both films share an underlying theme: confronting death in ways that force the characters to reflect on their lives, relationships, and personal identities. While Taste of Cherry offers a deeply contemplative exploration of life’s fragility, Death at a Funeral uses a comedic backdrop to explore similar existential struggles in a family gathering for a funeral.

The plot centers around a dysfunctional family who comes together to mourn the death of their patriarch, only for a series of chaotic events to unfold. The film's humor emerges from the awkward, unpredictable situations that arise—from misunderstandings about the deceased’s secret past to bizarre occurrences involving the funeral itself. What could have been a simple, sad event becomes a stage for exploring how each character deals with grief, familial expectations, and personal regrets.

Much like Taste of Cherry, Death at a Funeral challenges its characters to face uncomfortable truths about themselves and their relationships with the deceased. While Kiarostami’s film dwells in the silence of introspection, Oz’s work brings to life the emotional complexity of familial bonds, resentment, and the chaos that can surface when confronted with death. Both films explore the tension between life’s fragility and the often unpredictable nature of the human experience.

The family dynamic in Death at a Funeral is rife with emotional baggage—rivalries, repressed feelings, and long-held grievances. These elements echo the thematic core of Taste of Cherry, where Mr. Badii's journey reflects not just his despair but also the unresolved issues and emotional undercurrents in the people he encounters. In both films, the characters’ interactions are shaped by their personal histories with death, forcing them to grapple with questions of identity, morality, and the meaning of life.

Although Death at a Funeral leans more on the absurdity of human behavior, like Taste of Cherry, it encourages viewers to reflect on life’s fleeting nature, using humor to process profound emotional truths. It’s a stark reminder that, even in the face of the absurd, the contemplation of death is universal and unavoidable.

For those who appreciated Taste of Cherry’s deep dive into mortality, Death at a Funeral provides a refreshing contrast. It allows for moments of levity while still grappling with the emotional intricacies of loss and the inevitable impact death has on those left behind. Whether it’s the poignant moments of personal revelation or the chaotic family dynamics, this film offers a unique and engaging exploration of how we confront mortality, making it a fitting recommendation for fans of Kiarostami’s work.

The Farewell (2019)

The Farewell is a deeply personal exploration of how families cope with death—and how cultural differences shape how we experience grief. The film follows Billi, a young Chinese-American woman (played by Awkwafina), who returns to China under the pretense of a wedding when, in fact, the family is gathering to say goodbye to their beloved matriarch, Nai Nai, who has been diagnosed with terminal cancer. In a poignant twist, the family has decided not to tell Nai Nai the truth about her condition, believing that the knowledge would only bring her unnecessary sorrow.

Much like Taste of Cherry, The Farewell contemplates the intersections of life and death but with a focus on the emotional weight of family secrets, cultural expectations, and the complexity of relationships. While Kiarostami’s film focuses on one man’s solitary journey toward the end of his life, The Farewell highlights the collective experience of dealing with death within a family, where each member copes with the impending loss in their own way.

The central theme of The Farewell is the tension between individual desires and familial duty. Billi’s internal conflict about whether to reveal the truth to her grandmother forms the emotional core of the film. This delicate balance of truth, love, and sacrifice is explored in a way that resonates with the universal human experience. Just as Taste of Cherry delves into Mr. Badii's quest for meaning and his complex relationship with the people he encounters, The Farewell also explores the profound emotional depth of human connections, albeit through the lens of a family grappling with the lies they tell to protect their loved ones.

Both films take a restrained, minimalist approach to storytelling. Taste of Cherry features long, quiet shots that allow the viewer to sit with Mr. Badii’s internal struggle, while The Farewell is filled with moments of silence and pauses, where the characters’ emotions are often more pronounced through what is unsaid than through dialogue. The understated tone of both films invites viewers to reflect deeply on the fragile nature of existence and the complex ways in which death impacts not only the individual but also the collective.

What makes The Farewell especially compelling is its delicate exploration of cultural nuances around death. In Western culture, death is often a time for transparency and mourning, while in The Farewell, the family’s decision to keep the truth hidden stems from a deeply ingrained belief that it’s better to shield loved ones from unnecessary pain. This cultural difference offers a fresh perspective on the universal themes of mortality and how we choose to confront it, making The Farewell a fascinating and enriching companion to Taste of Cherry.

For those who appreciated Kiarostami’s exploration of death and the search for meaning, The Farewell offers a different yet equally profound meditation on life’s final moments. The film invites us to consider the relationships that shape our existence and the lengths we go to in order to protect those we love from pain, even when the truth is unavoidable. It’s a poignant reflection on the complexities of family, loss, and the love that binds us, making it an essential watch for anyone drawn to films that explore the intersection of life and death with sensitivity and depth.

Ordinary People (1980)

At its heart, Ordinary People is a poignant portrait of a family struggling to cope with the aftermath of a devastating loss. The film follows the Jarrett family—parents Calvin (Donald Sutherland) and Beth (Mary Tyler Moore), and their teenage son Conrad (Timothy Hutton)—as they attempt to navigate the emotional fallout after Conrad’s older brother, Buck, tragically dies in a boating accident. While Conrad’s father, Calvin, is emotionally open and caring, his mother, Beth, is distant and cold, unable to express her grief in any meaningful way.

This emotional divide between the family members is at the core of the film, and it draws a parallel to the quiet existential tension present in Taste of Cherry. Like Mr. Badii’s journey in Taste of Cherry, Conrad is searching for a way to reconcile his internal turmoil and find peace after a traumatic experience. But unlike Mr. Badii, who contemplates death as a means of escape, Conrad is struggling to live with the weight of survival—feeling guilty for having survived the accident that claimed his brother’s life.

Ordinary People deals with grief in a nuanced and realistic way, showing how different family members experience and cope with loss in their own ways. The film’s portrayal of the emotional struggles within a family, particularly the disconnection that often arises when individuals are unable to communicate their pain, aligns closely with the themes explored in Taste of Cherry. Both films delve into the isolation that accompanies grief, even within the context of familial bonds.

Conrad’s journey toward healing and self-forgiveness is mirrored in his relationship with his therapist, Dr. Berger (Judd Hirsch), who helps him confront his feelings of guilt and inadequacy. The therapeutic relationship in Ordinary People serves as a counterpoint to the more solitary experience of Mr. Badii, whose encounters with strangers reflect his quest for a resolution to his existential crisis. In contrast, Conrad’s road to healing is less about ending his life and more about learning how to live again, to confront the complexities of his emotions and the unresolved grief that has marked his family life.

The film’s muted pacing, spare dialogue, and understated performances echo the minimalist style of Taste of Cherry. Ordinary People does not rely on grand gestures or melodrama to convey its emotional weight. Instead, it is the quiet moments—the glances, the silences, the unspoken words—that reveal the depth of each character’s struggle. This subtle approach allows the audience to experience the characters’ emotional journeys intimately, much like the reflective pacing of Kiarostami’s film invites viewers to sit with Mr. Badii’s quiet contemplation.

At its core, Ordinary People is a meditation on the fragility of life and the difficulty of finding peace in the wake of tragedy. Much like Taste of Cherry, it explores the emotional aftermath of a life-altering event and examines how individuals seek meaning and solace in the face of loss. However, while Taste of Cherry presents an external journey, Ordinary People is grounded in the internal struggles of its characters, particularly the young Conrad, whose path to healing is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit.

For those who were moved by the introspective themes of Taste of Cherry—particularly the film’s exploration of existential despair, grief, and the human search for meaning—Ordinary People offers a similarly profound, though differently framed, exploration of how individuals cope with loss. Both films ask important questions about the meaning of life and death, and both challenge the viewer to reflect on their own relationships, personal grief, and the difficult task of moving forward after tragedy. If you're drawn to films that explore the subtle, often painful realities of human existence, Ordinary People is an essential and compelling watch.

Wild Strawberries (1957)

In Wild Strawberries, we follow Dr. Isak Borg (played by Victor Sjöström), an aging, emotionally distant professor of medicine, as he embarks on a road trip to receive an honorary degree. During the journey, he experiences a series of vivid, surreal dreams and flashbacks, which force him to confront the regrets, failures, and missed opportunities of his life. As he reflects on his past, Borg is also forced to face his own impending death, symbolizing the quiet inevitability of mortality that pervades Taste of Cherry.

Much like Mr. Badii in Taste of Cherry, Dr. Borg is at a crossroads in his life, struggling with the weight of his own existential concerns. However, while Mr. Badii's journey is driven by a desperate search for someone who will assist him in ending his life, Dr. Borg is confronted with the emotional cost of living—how his detachment, ambition, and neglect of relationships have led to a life filled with regret.

Bergman’s film intricately weaves between reality and dream, using surreal sequences to capture the inner turmoil of its protagonist. The contrast between Borg's cold, rational exterior and the emotional warmth he begins to experience as he reflects on his past mirrors the tension between Mr. Badii’s outward stoicism and his internal emotional crisis. Both characters are grappling with their own personal crises, seeking answers to deep existential questions about life’s meaning in the face of death.

Wild Strawberries is not just about an individual coming to terms with the idea of death; it is also about the profound impact that relationships—especially those with family—can have on our understanding of life and legacy. Borg’s interactions with his family, particularly his son-in-law and granddaughter, serve as a poignant reminder of how the choices we make throughout our lives affect those around us, even as we near the end. In a way, this mirrors the fleeting, introspective encounters in Taste of Cherry, where Mr. Badii meets various individuals on his journey, each representing a different perspective on life and death.

The film’s pacing, similar to Taste of Cherry, is deliberate and reflective. There are no grandiose actions or dramatic confrontations; instead, it is the quiet, contemplative moments that matter. Dr. Borg’s growing realization that he has lived a life disconnected from emotional truth and the regret that follows provides a powerful meditation on the themes of alienation and missed opportunities. These are emotions and experiences that Taste of Cherry explores in a much more isolated context, with Mr. Badii facing his existential crisis largely alone, while Borg confronts his through dreams and encounters with others on his journey.

One of the most powerful aspects of Wild Strawberries is how it portrays the passage of time. Borg’s dreams allow him to relive moments from his past and see them from a new perspective—suggesting that time changes not only physically but also emotionally as we come to understand the choices we’ve made. This exploration of time and memory is not dissimilar to Mr. Badii’s quiet reflections on the past as he considers whether his life has been worth living or if there is any meaning left in the time he has left.

Like Taste of Cherry, Wild Strawberries is a film that doesn’t offer simple answers but instead invites the viewer to reflect on their own relationship with mortality, the choices they’ve made, and the meaning they find in life. Both films are meditations on the emotional complexities of living and dying, and both ask the audience to confront the inevitability of death—not with fear or anger, but with a deeper understanding of what makes life truly meaningful.

For those who were captivated by Taste of Cherry’s exploration of personal meaning, Wild Strawberries offers a similarly rich, contemplative narrative. Both films are perfect for viewers interested in the delicate balance between life and death, as well as the emotional and existential struggles that define the human experience. Whether through Dr. Borg’s introspective journey in Wild Strawberries or Mr. Badii’s quest for peace in Taste of Cherry, these films challenge us to look inward and consider what it truly means to live a fulfilling life, even in the face of inevitable mortality.

In the Bedroom (2001)

In the Bedroom is a quiet, powerful drama that follows the lives of Ruth (Sissy Spacek) and Matt Fowler (Tom Wilkinson), a middle-aged couple whose life in a small Maine town is turned upside down after the tragic death of their son, Frank (Nick Stahl). Frank, a college student, had been involved in a complex and tumultuous relationship with a much older woman, Natalie (Marisa Tomei), who was involved in a fatal altercation with her abusive husband. After Frank’s death, Ruth and Matt are forced to come to terms with the grief, anger, and complex emotions surrounding his tragic end while also navigating the strained and uncertain future of their relationship.

Much like Taste of Cherry, In the Bedroom explores the weight of loss, the fragile nature of existence, and the difficult emotional terrain that follows the death of a loved one. Both films center around characters who are grappling with the aftershocks of a significant loss—whether it be the loss of a loved one, or the potential loss of life itself—and the emotional and psychological turmoil that accompanies these events.

While Taste of Cherry is largely concerned with a solitary man’s search for peace in the face of death, In the Bedroom examines how loss and grief shape the lives of those left behind. The film is an intimate exploration of how tragedy forces its characters to confront their deepest fears, regrets, and desires as they try to navigate the complexities of mourning while also dealing with unresolved emotions and buried conflicts. Both films underscore the fragile and fleeting nature of life and offer a meditative, quiet reflection on how individuals respond to the inevitable presence of death in their lives.

The film’s tone is understated, with much of the emotional weight carried by the performances of the cast and the quiet, restrained pacing of the narrative. Similar to the minimalist style of Taste of Cherry, In the Bedroom uses long, lingering shots to capture the tension between its characters, focusing on subtle, non-verbal exchanges that convey the deep emotional rifts caused by grief. In particular, Spacek and Wilkinson's portrayal of two people is heartbreaking, not only because of the tragic loss of their son but also because of the erosion of their own relationship as they attempt to cope with the aftermath.

Where Taste of Cherry finds its narrative momentum through Mr. Badii’s interactions with strangers during his journey, In the Bedroom delves deeper into the emotional devastation of its central couple. The film’s examination of Ruth and Matt’s evolving relationship in the wake of their son’s death provides an emotional core that is both heartbreaking and deeply relatable. Like Mr. Badii, Ruth and Matt are forced to re-examine their own lives, their choices, and what they want from their futures. They, too, must wrestle with how much control they have over their own lives and whether it is possible to find peace after experiencing such profound loss.

One of the most powerful aspects of In the Bedroom is its portrayal of the unpredictable nature of grief. The film illustrates how loss can trigger unexpected responses—whether it is Ruth’s stoic approach to mourning or Matt’s more impulsive desire for revenge and justice. In many ways, these conflicting emotions mirror the existential questioning found in Taste of Cherry, where Mr. Badii is uncertain whether his life has meaning or if he should simply end it. Both films deal with the uncertainty that accompanies death—how it forces us to face difficult choices and how our understanding of life is often shaped by the tragedies we endure.

The film’s slow, deliberate pace, similar to Taste of Cherry, encourages viewers to reflect on the emotional and psychological consequences of the events unfolding. There are no easy answers or dramatic resolutions in In the Bedroom; instead, it leaves the audience with a sense of unresolved tension, much like the quiet, ambiguous ending of Taste of Cherry. Both films ask the viewer to confront the complexity of the human experience and the emotional toll that comes with facing life’s most profound questions.

Like Taste of Cherry, In the Bedroom is a film that resonates deeply because of its unflinching exploration of human emotion in the face of tragedy. It doesn’t shy away from the complexities of grief, and it offers a sobering yet cathartic portrayal of the ways in which we cope with loss. For viewers who appreciate the quiet intensity and emotional depth of Taste of Cherry, In the Bedroom is a film that invites a similarly reflective examination of life’s most difficult and transformative moments.

Babyteeth (2019)

Babyteeth is a poignant coming-of-age story that follows Milla (Eliza Scanlen), a 16-year-old girl who is diagnosed with terminal cancer. As she grapples with her illness, Milla forms an unlikely and turbulent relationship with Moses (Toby Wallace), a troubled drug addict, and begins to explore the complexities of love, family, and the fleeting nature of life. The film balances lighthearted moments with devastating emotional depth, offering a nuanced portrayal of how individuals confront their mortality in unexpected ways.

Much like Taste of Cherry, Babyteeth tackles the theme of mortality head-on, though with a different approach. While Kiarostami’s film centers around an older man, Mr. Badii, seeking peace through death, Babyteeth explores the vibrant and often chaotic experience of youth in the face of terminal illness. Despite the contrast in their approaches, both films share a deep interest in how people reckon with death and what they choose to value when life is coming to an end.

The film’s blend of dark humor and raw emotional exploration resonates with the introspective and meditative tone of Taste of Cherry. Milla’s journey—her rebelliousness, her search for purpose, and her passionate experiences—offers a poignant counterpoint to the quiet, deliberate reflections of Mr. Badii. Whereas Kiarostami’s film takes a minimalist, almost austere approach to its subject matter, Babyteeth embraces a more vibrant and, at times, chaotic portrayal of life in the face of death, infusing the narrative with moments of joy, love, and even absurdity.

Both films also delve into the complexity of human relationships. Milla’s relationship with Moses is both tender and destructive, marked by the stark contrasts between her desire to live freely and the constraints imposed by her illness. Similarly, Mr. Badii’s encounters with strangers in Taste of Cherry highlight the ways in which our interactions with others shape our understanding of life, death, and the meaning of existence. Both films reflect on how love, human connection, and existential questioning are inextricably linked, showing that while life can be fleeting and uncertain, it is these very connections that provide a sense of purpose and belonging.

While Taste of Cherry is understated in its exploration of life and death, Babyteeth uses its vibrant characters and raw emotional dynamics to portray a different aspect of the human experience. In Taste of Cherry, silence and simplicity allow the viewer to focus on Mr. Badii’s internal struggle, while Babyteeth uses its dynamic characters, witty dialogue, and colorful visual style to create a more emotionally charged and unpredictable narrative. Despite these differences in tone and style, both films offer powerful meditations on the fragility of life and the importance of finding meaning in the face of inevitable loss.

The emotional depth of Babyteeth is underscored by outstanding performances from its cast, particularly Eliza Scanlen, whose portrayal of Milla is both vulnerable and fierce. Her character’s journey of self-discovery, emotional turmoil, and grappling with death mirrors the reflective journey of Mr. Badii, even if the emotional landscape is much more chaotic and tumultuous. Moses, played by Toby Wallace, provides an intriguing contrast to Milla, bringing a sense of unpredictability and danger to their relationship yet also contributing to Milla’s exploration of her desires, dreams, and the search for meaning in the face of an uncertain future.

Babyteeth also touches on themes of family dynamics and the emotional toll of illness. Milla’s parents, played by Ben Mendelsohn and Essie Davis, are forced to navigate the emotional complexity of caring for a terminally ill child while dealing with their own personal struggles. This adds an additional layer to the film, as it highlights the different ways in which individuals react to the impending loss of a loved one. Like Taste of Cherry, the film asks the question of how we, as individuals and as families, cope with the inevitability of death—and whether we can find peace, connection, or even joy in the face of it.

In many ways, Babyteeth is a vibrant exploration of how individuals search for meaning and purpose in the face of life’s most profound questions. While its tone may be more emotionally volatile and unpredictable than the stillness of Taste of Cherry, both films encourage introspection and contemplation of the fleeting nature of life. They compel the viewer to reflect on their own relationships, desires, and choices, urging them to ask: How do we live with the knowledge of our mortality? And how do we find meaning in a world that is often fleeting and uncertain?

Amour (2012)

In Amour, a retired couple, Georges and Anne, face the profound emotional and physical toll of Anne's debilitating stroke. The film takes an unflinching look at how the couple’s relationship evolves as Anne’s condition worsens, forcing Georges to care for her in increasingly difficult circumstances. The film’s slow, deliberate pacing and long, intimate takes mirror the reflective nature of Taste of Cherry, both offering poignant meditations on mortality, the challenges of human connection, and the profound implications of personal loss.

Much like Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry, Amour examines the question of how individuals reconcile themselves to death and the fragility of life. However, while Taste of Cherry focuses on the contemplation of death from the perspective of someone considering taking their own life, Amour presents the emotional and physical realities of caregiving in the final stages of life. In Amour, the reality of Anne’s impending death forces both her and Georges to confront not only the end of life but also their deep, unwavering connection that has lasted throughout their marriage.

The film's emotional depth and sensitivity to the process of aging and illness share thematic ground with Kiarostami’s approach in Taste of Cherry. Both films grapple with how individuals relate to the inevitable end of life, yet Amour centers on the endurance of love in the face of suffering. Georges’s commitment to Anne, despite the immense physical and emotional toll, speaks to the complexities of human relationships—love, duty, and sacrifice—that are often brought into sharp focus when confronted with death.

Like Taste of Cherry, Amour does not offer easy answers. There are no grandiose emotional outbursts or cinematic flourishes. Instead, both films invite the audience to reflect quietly on life’s most profound questions—what makes life worth living? What are we willing to endure for love? And, perhaps most importantly, how do we find peace when death is an inescapable reality?

The minimalist nature of Amour—its sparse dialogue, slow pacing, and absence of melodrama—also mirrors Kiarostami’s use of silence and simplicity in Taste of Cherry. Both films create an atmosphere of contemplation, where every interaction, every gesture, and every word becomes laden with emotional weight. Amour is a meditation on the painful beauty of human existence, and its portrayal of a couple's final months together is as deeply moving and introspective as Mr. Badii’s search for meaning in Taste of Cherry.

A striking aspect of Amour is its exploration of the slow decay of the body and the effect this has on both the person who is dying and their loved ones. Georges’s caregiving and his increasing isolation as he faces the reality of Anne’s deteriorating condition mirror the emotional landscape of Taste of Cherry, where Mr. Badii’s encounters with others highlight the internal battles between life, death, and what lies beyond. Georges, like Mr. Badii, is forced to question what it means to live, what it means to die, and how one can come to terms with the loss of a loved one.

Both films also explore the idea of surrender. In Taste of Cherry, Mr. Badii seeks a willing participant to assist him in ending his life, struggling with the choice of whether he should face the end on his own terms. In Amour, Georges is forced into a similar form of surrender as he watches his beloved wife deteriorate, ultimately making the agonizing decision to care for her in her final days, even as it strains him beyond his limits. In both cases, the characters wrestle with powerlessness in the face of death and the need to find some form of agency in their final moments.

Despite its heavy subject matter, Amour offers moments of tenderness and beauty, reminding the audience that even in the face of immense pain and suffering, the human spirit can find solace in connection and love. This nuanced, contemplative approach to life and death is what makes Amour an excellent follow-up for viewers who were moved by Taste of Cherry. Both films invite viewers to reflect on the complex emotional terrain of life’s final stages, encouraging them to appreciate the fleeting beauty of existence and the relationships that give it meaning.

Ikiru (1952)

In Ikiru, the protagonist, Kanji Watanabe, is a middle-aged bureaucrat who receives the devastating news that he has terminal cancer. This stark revelation forces him to reassess his existence, which has been dominated by decades of monotonous, meaningless work. What follows is a deeply moving exploration of the human capacity for transformation in the face of death.

The film's central theme, like Taste of Cherry, grapples with the idea of life's meaning, particularly when it seems to be slipping away. Kanji's realization that he has wasted his life on a series of small, unimportant tasks forces him to ask himself what truly matters. As he reflects on his past, he embarks on a quest to find purpose in his final months, ultimately deciding to dedicate himself to building a playground for children in a neglected area of the city.

Much like Taste of Cherry, Ikiru is a reflection of what it means to live a life worth living. The film poses the question: How does one find meaning when faced with the inescapable reality of death? Kanji’s search for purpose resonates with the internal conflict faced by Mr. Badii in Taste of Cherry, who also struggles with the idea of ending his life in a moment of despair. However, while Mr. Badii seeks release from his pain, Kanji chooses to take action, attempting to leave a meaningful legacy before his time runs out.

Both films explore the paradox of life and death through deeply personal stories. Ikiru's portrayal of a man’s search for redemption in his final days is remarkably similar to Taste of Cherry’s meditation on mortality. The contrast between Kanji’s last-ditch efforts to make a difference and Mr. Badii’s desperate quest for escape creates a poignant dialogue between two different responses to an existential crisis. In both cases, the protagonists are ultimately confronted with the painful question: What have I truly done with my life?

Kurosawa’s minimalist approach to storytelling, much like Kiarostami’s, focuses on quiet, intimate moments that emphasize the emotional weight of the characters’ decisions. Both films use silence and simplicity to convey deep emotional truths. While Ikiru explores the themes of legacy and redemption, it also captures the intense loneliness and isolation that often accompany the knowledge of one's impending death, much like Taste of Cherry does.

One of the most striking aspects of Ikiru is its ability to blend stark realism with profound philosophical questions. The film’s narrative takes the viewer on a journey from the initial shock of Kanji’s diagnosis to his attempts to find meaning in the face of inevitable death. In his final months, Kanji’s actions, though small in the grand scheme of life, take on immense significance. His journey from apathy to purpose echoes Mr. Badii’s journey of self-reflection and his search for answers to life’s most profound questions.

Another powerful connection between Ikiru and Taste of Cherry is the sense of solitude that both protagonists experience. Kanji's life has been spent in a haze of bureaucracy, surrounded by people yet utterly disconnected from them. Similarly, Mr. Badii’s encounters with strangers on his quest to end his life highlight the isolation that often accompanies personal struggles. Both characters are grappling with the question of their place in the world, and in both films, their interactions with others become key to their understanding of themselves and their final decisions.

While the tone of Ikiru is more somber than Taste of Cherry, it also conveys a sense of hope that emerges from the despair of facing one's mortality. Kanji’s transformation, his eventual realization that he can make a meaningful impact in his last days, offers a message of redemption. In contrast, Taste of Cherry leaves viewers with a more ambiguous conclusion, one that raises questions rather than offering definitive answers. Both films, however, invite audiences to reflect on the complexity of life and death and the decisions that shape our understanding of existence.

Ultimately, Ikiru and Taste of Cherry share a common thematic thread—the search for meaning in the face of death. Both films depict the struggles of individuals as they confront their mortality and the existential void that often accompanies it. Whether through a quest for self-destruction or a quest for redemption, the characters in these films compel us to consider our own relationships with life, death, and the choices that define us.

The films listed here all share thematic ties with Taste of Cherry, exploring the complexities of death, personal identity, and the search for meaning in life. From the slow, meditative reflections of A Ghost Story to the surreal musings of Synecdoche, New York, each of these films delves into profound existential questions. They invite viewers to reflect on their own lives, urging them to consider what makes life worth living and how to reconcile with the certainty of death.

Despite their shared thematic concerns, these films offer a rich diversity of tone—from the dark and introspective, like Melancholia, to the uplifting and humorous, as seen in The Bucket List. This range ensures that the exploration of mortality remains multifaceted, reflecting the varied emotional responses we have when faced with life’s fragility.

For those who found resonance in Taste of Cherry, these films provide additional reflections on death, grief, and the human experience. Whether through stark realism, surreal narratives, or heartwarming drama, each film invites its audience to reflect on life’s meaning and the choices we make in the face of our mortality. These films not only entertain but also challenge viewers to think deeply about the nature of existence and the inevitable end that awaits us all.

Movies Like Taste of Cherry

Drama,Comedy Movies

- 22 Movies Like Call Me By Your Name | Similar-List

- Discover 10 Rom-Com Movies Like How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days

- Top Picks: Action Movies like Bullet Train | Similar-List

- 15 Must-Watch Movies Like Ready Or Not | Similar-List

- Romantic Movies Like Beautiful Disaster | Similar-List

- Racial Harmony Movies Like Green Book | Similar-List

- Movies that Feel Like Fall: 20 Must-Watch Films | Similar-List

- 21 Best Movies Like The Truman Show

- 16 Movies like My Fault you must watch

- 10 Heartfelt Movies Like A Walk to Remember | Similar-List

- Laugh Riot: Top 10 Movies like Ted

- 16 Best Movies Like Juno

- Laugh Riot: 10 Films Echoing 'Movies Like White Chicks'

- Enchanting Picks: 10 Family Movies Like Parent Trap | Similar-List

- 10 Best Movies Like She's The Man

- 10 Best Movies like 500 Days of Summer

- 10 Epic Movies Like Lord of the Rings | Similar-List

- Rhythm & Intensity: Movies like whiplash| Similar-List

- 10 Best Movies Like The Big Short

- Teen Comedy Movies Like The Girl Next Door | Similar-List

More Movies To Add To Your Queue

- 22 Movies Like Call Me By Your Name | Similar-List

- Timeless Romances: 10 Movies like About Time | Similar-List

- Top 20 Movies Like Twilight to Watch in 2024 | Similar-List

- 20 Thrilling Adventures Movies Like Hunger Games | Similar-List

- Discover 10 Rom-Com Movies Like How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days

- 15 Enchanting Movies Like Harry Potter | Similar-List

- Thrills Await: Explore Movies Like Us | Similar-List

- Top Picks: Action Movies like Bullet Train | Similar-List

- 12 Beloved Musical Movies like La La Land | Similar-List

- 15 Must-Watch Movies Like Ready Or Not | Similar-List

- 20 Movies Like Everything Everywhere All At Once | Similar-List

- Romantic Movies Like Beautiful Disaster | Similar-List

- Racial Harmony Movies Like Green Book | Similar-List

- 18 Best Erotic Romance Movies Like 9 Songs

- Discover Movies Like Wind River 2017 | Similar-List

- Apocalyptic Alternatives: 15 Movies like Greenland | Similar-List

- Movies that Feel Like Fall: 20 Must-Watch Films | Similar-List

- Movies Like Zero Dark Thirty: A Riveting Journey | Similar-List

- 21 Best Movies Like The Truman Show

- 16 Movies like My Fault you must watch

You May Also Like

- The 20 Best Movies Like Level 16 | Similar-List

- Chilling Horror Picks: Movies Like The Strangers

- Hilarious Teen Comedies: Movies Like Superbad

- 20 Best Movies Like Wedding Season

- 20 Must-Watch Movies Like Mr. Peabody & Sherman | Similar-List

- Discover Other Compelling Movies Like My Old Ass

- 20 Thrilling Movies Like Sinister 2

- 8 Best Movies Like Parasite | Similar-List

- 19 Thrilling Movies Like War of the Worlds | Similar-List

- 10 Best Movies Like The Big Short

- Top 20 Movies Like Sanctuary

- Top 19 Movies Like Kill You Should Watch | Similar-List

- 20 Adventures Movies Like The Last of the Mohicans | Similar-List

- Top 20 Movies Like Project Almana You Must Watch

- 10 Mystery Movies Like See How They Run | Similar-List

- 20 Must-Watch Movies Like The Adam Project | Similar-List

- Top 10 Movies Like Monkey Man You Must Watch | Similar-List

- 20 Best Movies Like Project Power

- 20 Best Movies Like Just Mercy | Similar-List

- 21 Thrilling Movies Like Never Back Down | Similar-List